What is consciousness? What is the relationship between mind and brain? How did complex structures evolve out of a random collection of molecules? Such questions, among others, have flummoxed philosophers and scientists alike, since the dawn of civilization. They still do — notwithstanding a host of triumphant, even breathtaking discoveries, that include peptides, our molecules of emotions. This isn’t all. Molecular biologists have discovered the fundamental building blocks of life, and also unraveled the human genetic code. Yet, the amazing scientific realization has not helped them to fully understand the vital, integrative repertoire, or interconnected orchestrated “jazz” of living organisms.

Agreed that new concepts in physics, for instance, have brought about profound, mind-boggling changes — transforming the mechanistic worldview of René Descartes and Isaac Newton into a holistic, natural view. Yet, this novel vision of rational reality was, or is, by no means easy to accept. New scientific advances have certainly brought scientists into contact with a strange and not-so-expected reality, yes; but, it has also presented them with a paradoxical allegory. In their struggle to grasp this new reality, they have become painfully aware too that their basic concepts and language, including their “time-tested” whole new way of thinking were, or are, inadequate to describing the atomic phenomenon.

This new paradigm shift or holistic worldview is, of course, accepted as scientific and also spiritual. As physicist Fritjof Capra explains, “When the concept of the human spirit is understood as the mode of consciousness in which the individual feels a sense of belonging, of connectedness, to the cosmos as a whole, it becomes clear that ecological awareness is spiritual in its deepest sense, essence. It is, therefore, not surprising that the emerging new vision of reality based on deep ecological awareness is consistent with the so-called perennial philosophy of spiritual traditions, whether we talk about the spirituality of Christian mystics, that of Buddhists, or the philosophy and cosmology underlying the Native American traditions.”

A full “organismic” conception of biology, for instance, or the belief that in every complex system the behavior of the whole can be understood essentially from the properties of its parts, is central to medieval thought — or, Descartes and his celebrated, albeit outdated, method of “analytical” thinking. Modern science has reversed the relationship. Systems, as we now understand, cannot be understood by analysis alone. In other words, it only means that the myriad properties of the parts are not intrinsic entities; they can be appreciated, for the most part, within the context of the larger whole.

The old Cartesian line of thinking relates to scientific description as objective — that is, independent of the human observer and the process of knowing. To quote Capra, again, “The new paradigm implies that epistemology — understanding of the process of knowing — has to be included explicitly in the description of natural phenomenon.” This is principally because systems are all interdependent. You may also exemplify them as a network of relationships, including nature, with a corresponding arrangement of concepts and models, none of which is any more fundamental than the others.

Knowledge is relative and not absolute — any which way you look at it. The new paradigm is in tune with such a thought which originates from ancient Indian philosophy; logically too. It recognizes that all scientific concepts and theories are limited and approximate; and, that science cannot always provide a complete and/or definitive understanding.

This takes us to the pioneering work of polymath Alexander Bogdanov and the formulation of his groundbreaking concept called “tektology”. By using the terms “complex” and “system” interchangeably, Bogdanov distinguished three kinds of systems — organized complexes, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts; disorganized complexes, where the whole is smaller than the sum of its parts; and, neutral complexes, where the organizing and disorganizing activities revoke each other.

Throughout the history of philosophy and science, there’s been a stressful relationship between the study of substance and the study of form. Well, if the study of substance began in Greek antiquity, we have now come a long way — from the idea of four fundamental elements — earth, air, fire and water — to atoms, cells, enzymes, proteins, amino acids and so on.

You’d call them the study of patterns, to be precise. For the simple reason — the study of patterns is too crucial to understand living systems. More so, because systemic properties tend to often emerge from a configuration of “ordered” relationships. This is no less a simple, profound truth. Because, there’s sure something about life, something non-material, even irreducible — a pattern of organisation.

The human brain, to cull a fascinating example, is probably the most complex structure in the known universe — it encompasses our every thought, action, memory, feeling and experience of the world.

The brain, which is more complex than the galaxy, weighs just around 1.4 kg, and yet it contains an astounding one hundred billion nerve cells, or neurons. Each neuron can make contact with thousands or even tens of thousands of others by means of minuscule structures called synapses.

As Stephen Smith, a professor of molecular and cellular physiology, Stanford University, US, says, “One synapse may contain 1,000 molecular-scale switches; a single human brain has more switches than all the computers, routers and Internet connections on earth.” To accentuate the metaphor, you’d imagine the brain as a complex area covered by a “similar” number of house bricks covering about 600 sq km in size. The complexity of the connectivity between brain cells, you’d agree, is no less astonishing. The best part is our brains form a million new connections for every second of our lives, while the pattern and strength of such connections is all the time changing. More importantly, no two brains are alike — they are as distinctive, or unique, as our fingerprint or signature. It is precisely in such changing connections that memories are also made of and stored, habits learned and personalities shaped, while reinforcing, or “ringing-in” certain patterns of brain activity and “ringing-out” others.

The view of living systems as self-organizing networks, whose components are all interconnected and interdependent, has been well expressed since the beginning of time. However, precise, detailed models of such systems came to be formulated in the recent past, thanks to new mathematical tools. This new, novel “mathematics of complexity” has allowed scientists to model non-linear interconnectedness — that epitomize characteristics of networks — with the help of high-speed computers. This could have made good, old Galileo Galilei proud; so also Plato and Descartes, the initiator of modern, now modified, Western philosophy.

The process of living is not the world, but a world — one that is always dependent on interdependent structures — be it human beings, language, thought or consciousness, including the genetic information encoded in our DNA. The most important point is we can understand human consciousness primarily through semantics and the whole social context in which it is embedded in its Latin root, “consilience.” Consilience, a term coined by biologist Edward Wilson, signifies the idea of “knowing together”. It connotes the interconnectedness of all things in the universe — and, that consciousness is, in essence, a social phenomenon.

What does this signify? That to be human is to be endowed with reflective consciousness — of body movements which become tightly linked in a complex dance of behavioral co-ordination. Of the multitude forms we perceive, brought forth by the divine actor and magician, and not a figment of our imagination — call it god or Supreme Being, and the dynamic force of participation called “karma”. One that ancient Indian thought explained with sublime finesse, “If this interplay, or involvement, was only an illusion, the law of ‘karma’ would have been a damp squib upon humanity.”

It sums up the sum total, and essence, of complexity, with a new vision of reality — a pragmatic web of life, including living systems, that envelops us all.

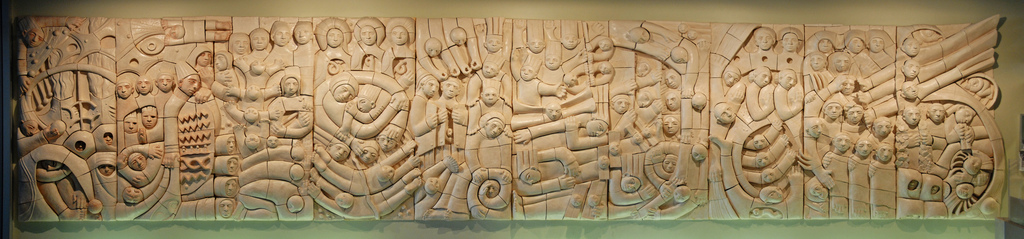

Photo Credit:

The Story of Life by Seb Przd via Flickr Creative Commons. Some rights reserved.

This article was first published in Financial Chronicle. It is reprinted here with full permission of the publisher.

© Financial Chronicle. Website: www.mydigitalfc.com

Please Share Your Thoughts - Leave A Comment!