John Keats’ legacy will live on — so long as poetry exists.

John Keats lived for just 25 years — and, yet, his literary reams of gold have left their imprint on the sands of time. As Percy Bysshe Shelley, another great poet, wrote, “He (Keats) has outsoar’d the shadow of our night;/Envy and calumny and hate and pain,/ And that unrest which men miscall delight,/Can touch him not and torture not again.” A celebrated tribute, Shelley’s encomium also implied that Keats was unique and different from his contemporaries.

John Keats lived for just 25 years — and, yet, his literary reams of gold have left their imprint on the sands of time. As Percy Bysshe Shelley, another great poet, wrote, “He (Keats) has outsoar’d the shadow of our night;/Envy and calumny and hate and pain,/ And that unrest which men miscall delight,/Can touch him not and torture not again.” A celebrated tribute, Shelley’s encomium also implied that Keats was unique and different from his contemporaries.

Keats was a Romantic poet. His literary flourish had Miltonian and Spenserian elements. He was a ‘Greek’ too; his genius secure in the principle of exquisite beauty. Ornate and full of life, Keats’ poetry expressed nature, its objectivity, subjective and mystical allegory, or verdant consciousness with Shakespearean resplendence. Although his life as a poet was far too short — a meagre three-plus years — Keats’ prodigious output is enough grist to knocking the daylights out of what we call as fuzzy logic, where machines can write interesting novels, screenplay and also poetry, in a selected style.

Keats (1795-1821) was a multi-sided craftsman untouched by the standard political questions of his time. A relentless experimenter, with a ken for moral, spiritual, emotional and soulful sensitivities, Keats took the sonnet, epic, narrative, and the ode, for the higher purposes of one’s literary existence. Everything, aside from his own perception of poetry, was fume for Keats. For a qualified surgeon, Keats could have also delighted in handling the scalpel, with the natural finesse of a poet. But, destiny was manifest when he gave up surgery in favour of his first love — poetry.

When Keats’ first sonnet, O Solitude, appeared in the Examiner, in 1816, the periodical’s editor, Leigh Hunt not only announced Keats’ literary merits, with much fanfare, but he also became the poet’s avid fan. Keats’ first major literary work, Poems, published the following year, was celebrated by his friends, albeit the effort was not a commercial success. More to the point, the legendary William Wordsworth, for one, to whom Keats sent an inscribed copy, did not flip through the pages. Yet another bemoaning thing was critical snobbery and gross indifference; it had had a ‘spilling’ influence on Keats’ literary endeavours for Endymion (1818).

Emotional Ennui

A sensitive man, with a none-too-happy personal and domestic life, Keats’ emotional ennui was seemingly too obvious. He lost his heart. In short, there was no meaning for him in life. Worse still, a rupture of a blood vessel in his lungs, juxtaposed by rapid consumption, hastened his untimely death. Savage disapproval was another, although what enfeebled his psyche the most was ‘domestic criticism,’ not to speak of the deride he was subject to — ‘literary canonisation.’ It is also believed that Keats poisoned himself with the catastrophic treatments of the time — dosing with mercury. Not that personal animosity and bias were unjustified. Keats was no god. He was human; prone to foibles. Endymion, his long poem, for instance, is too long — of four books of one thousand lines each. It is not only obscure in its wobbly imagery, but chequered in its narrative form. Keats took the ‘flak’ in his stride vis-à-vis Endymion, all right. This was also precisely the reason why he himself thought, at that point, his best was yet to come. It did, with glorious intent — by way of his subsequent poems.

A case in point was The Eve of St Agnes (1820), with its eternal beauty of sound and texture and brimming with a sense of fascinating narration as evocative as nature — in sum, an “eye feast and an ear feast.” The Eve… has all the trappings of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Sir Walter Scott’s Lochinvar — of mediaeval, also mindless, hostility of two feuding families, with a ‘self-sustaining’ never-say-die spirit and, more importantly, the devotion of two young lovers, a subject with endless universal appeal. What’s more, Keats’ narrative has a splash of musical and picture-postcard resonance and colour. Besides, his imagination is peppered with Spenserian nuance.

The Poetic Triad

Keats reached the pinnacle of his art with a poetic triad, Ode to a Nightingale (1819), Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819), and To Autumn (1819), among other works. Let’s savour just one gem: “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;/Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,/Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone.” All the same, existence and death, struggles, ugliness, poverty and wistful lamentation did not ‘inspire’ Keats. His poetry was not just vitality, it also had sheer impulse. It was a delicious opus for the senses — all by itself.

Keats’ nightingale, to cull a paradigm, was not a bird. It was to Keats the symbol of ecstasy. This was also his attitude to life, notwithstanding all his adversities. Life, to Keats, was a spiritual process and experience — a credo, through which James Redfield, the new ‘apostle’ of the soul, has made a stunning fortune. Keats lived in a different epoch, where money was scarce for a writer. For Keats, poetic flourish, was tantamount to spontaneity and truth, not financial recompense. In his words, “The rise, the progress, the setting of imagery, should like the sun come natural to him (the poet). If poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree, it had better not come at all.”

Keats’ concept of negative capability — or, sympathetic imagination — was another benchmark. It appeals to people who are not drawn to him too — even today. If this isn’t genius. what is — as Keats himself must have estimated with his Hyperion (1818) on his motif? Yet, typical of his own Keatsian realisation, Keats paradoxically gave up Hyperion, which was intended to be an epic in a dozen books, after the third volume. Reason? Far too many Miltonian elements and similes — or, ‘peer-centric’ disparagement.

Keats was far too conscious of unbalanced elements or overworked chemistry of literary razzmatazz, no less — despite everything. So, he judged his corpus of work in the best manner possible — simply, sensibly and without jargon. Not many authors, past or present, whatever their genre, have followed this ‘righteous’ philosophy, or outlook. Because, success is measured in terms of ingenuity — a ‘dogma’ that also extends to novelists who are not great writers? Perhaps. One outstanding exemplar, today, is John Grisham, who has the dreadful habit of concealing information and then unravelling it for a breezy plot-filled, best-selling humdinger.

This sums up Keats, a poet’s poet, whose name is writ large in gold, not just marble, on his tombstone in Rome. His alluring poetic legacy will live so long as poetry exists.

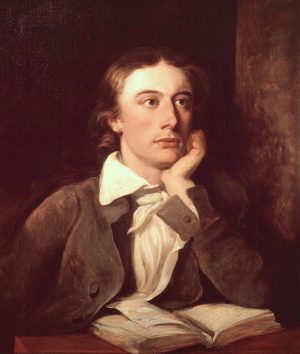

Photo Credit

John Keats by William Hilton – Wikimedia Public Domain

This article was first published in Madras Courier

Please Share Your Thoughts - Leave A Comment!