In times past, a clever pharaoh would earn kudos by dispatching a top specialist to a neighboring monarch. Of course, this sometimes backfired. Herodotus reports in his Histories that an eye specialist sent to the court of the Persian king, Cambyses, became so annoyed with his pharaoh for separating him from his family, that he incited the Persian monarch to successfully invade Egypt.

In another case Hero![18th dynasty pharaoh Ahkenaten is depicted as having a bizarre elongated gynecoid body shape [pear shaped] with a narrow face and long tapering digits.](../files/2010/09/ahkenaten-197x300.jpg) dotus tells how the Persian king Darius was about to execute all his Egyptian doctors for mishandling his injured ankle. The Greek doctor who successfully treated Darius implored the king to spare his colleagues, to which he agreed.

dotus tells how the Persian king Darius was about to execute all his Egyptian doctors for mishandling his injured ankle. The Greek doctor who successfully treated Darius implored the king to spare his colleagues, to which he agreed.

Perhaps we can attribute the 94-year-long reign of pharaoh Pepy II at least partly to the ministrations of his doctors. He is still on record as the longest ruling monarch in history beating out such notables as Victoria, Louis XIV and Franz Josef by many years.

On a recent trip to Egypt I had the opportunity to see and photograph various medically-related subjects ranging from artistic depictions of surgery and surgical instruments, to sculptures and paintings showing actual pathology.

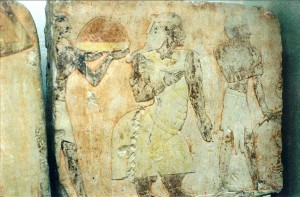

Perhaps the most ancient existing depictions of surgery are found in the Old Kingdom tomb of Ankh-Ma-Hor at Saqqara. Over 4000 years old, these reliefs depict surgical procedures on the toes and circumcision.

At the Temple of Kom Ombo in Lower Egypt, I came across a carved wall depicting an array of surgical instruments which would not look out of place in an OR today. This included a variety of scalpels, curettes, forceps and dilators, as well as scissors and medicine bottles. The Coptic Museum in Cairo has an actual display of bronze medical instruments of all types dating from the days of Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt.

There is no shortage of depictions of pathology in pharaonic Egyptian art. I came across several representations of achondroplastic dwarfism, including the famous sculpture of the dwarf Seneb and his family in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Seneb became an affluent and respected member of his society, indicating that his condition did not present an insurmountable barrier to advancement, even in ancient Egypt. I also found dwarves depicted making jewelry on the walls of an Old Kingdom tomb. They were reputed to be quite skilled at this craft, due to their tiny hands.

Touring the Egyptian Museum’s Amarna roo m one could be forgiven for thinking that theories of extra-terrestrial influences on ancient Egypt might actually be based on fact. The 18th dynasty pharaoh Ahkenaten is depicted as having a bizarre elongated gynecoid body shape [pear shaped] with a narrow face and long tapering digits.

m one could be forgiven for thinking that theories of extra-terrestrial influences on ancient Egypt might actually be based on fact. The 18th dynasty pharaoh Ahkenaten is depicted as having a bizarre elongated gynecoid body shape [pear shaped] with a narrow face and long tapering digits.

His six daughters were sculpted with oddly elongated heads. Some feel this was simply a new artistic convention, while others once believed Ahkenaten may have suffered from Marfan’s Syndrome. The latter theory seems to have been disproved by recent DNA evidence, however. This pharaoh introduced a revolutionary new monotheistic religion to ancient Egypt, which some think may have been a precursor to the Judeo-Christian religions. (Moses was certainly a common royal name at that time.)

Additionally, I found two pieces of art in the Egyptian Museum, which may represent cases of microfilariasis, a parasitic infestation that can block the lymphatic system. The result is huge distention of parts of the body, usually the legs. A seated statue of a Middle Kingdom pharaoh shows huge legs in relation to the rest of the body. Perhaps this was an artistic blunder or maybe the king suffered from so-called “elephantiasis” of his lower limbs.

Another possible examp le of this disease is a painted relief from a chapel of Queen Hatshepsut’s tomb which documents her trade expedition to Punt (probably present day Somalia). The Queen of Punt is shown as having a massive lower body which some speculate could be due to microfilariasis.

le of this disease is a painted relief from a chapel of Queen Hatshepsut’s tomb which documents her trade expedition to Punt (probably present day Somalia). The Queen of Punt is shown as having a massive lower body which some speculate could be due to microfilariasis.

As an aside, Queen Hatshepsut herself may represent an early example of transvestitism. Usurping power from her young nephew, Thutmoses III, she ruled as pharaoh for years, often having herself depicted as a man and sporting a beard. She also insisted in having a monument in the Valley of the Kings, as well as the Valley of the Queens.

A final example of disease found in the Egyptian Museum shows an individual with a marked kyphosis, [a marked curvature of the spine sometimes referred to as hunchbacked]. The male figure appears too young to be suffering from osteoporosis. Perhaps this is a congenital kyphosis, or perhaps it is due to pathological bone fracture from untreated infection. He does not seem to have enough of a twist to his spine to warrant the diagnosis of adolescent kypho-scoliosis.

As we can see from the accompanying photos, the ancient Egyptians had a lively interest and acquaintance with medicine and pathology. Many people today believe these ancient peoples laid the foundations for modern medical practice. Even today, whenever physicians write the Rx symbol, they are in fact asking the blessing of the god Horus, whose eye it represents.

Read more about ancient Egyptian medicine in George Burden’s previous Life As A Human article, “‘Doc’ Like an Egyptian.”

Photo Credits

All photos © George Burden

“Ahkenaten”

“Elephantiasis”

“Dwarfism”

“Kyphosis”

Thanks for your kind comments. You might find the previous posting, also concerning ancient Egyptian medicine, of interest.