My life is full of contradictions, or what I call my bi-polar activity. Not that I have some clinically diagnosed chemical imbalance in my aging grey matter; rather, unlike most of my friends whose work and home life are often inter-related, mine is completely disparate. When I work, it’s full on — 35 to 42 days every day, 14 hrs a day. And when I’m home for the same length of time, it’s up to me to keep busy.

My life is full of contradictions, or what I call my bi-polar activity. Not that I have some clinically diagnosed chemical imbalance in my aging grey matter; rather, unlike most of my friends whose work and home life are often inter-related, mine is completely disparate. When I work, it’s full on — 35 to 42 days every day, 14 hrs a day. And when I’m home for the same length of time, it’s up to me to keep busy.

I work in countries where a family visit isn’t even a remote possibility, so no one close to me ever sees how I make a living. I’m immersed for long periods in situations where I am fortunate to gain a unique insight to an industry, or a political issue which, when I come back home, generally places me in exact opposition to popular beliefs.

For example, I have a different viewpoint regarding the Alberta tar sands because I’ve flown over them, landed at various camps, and flown guided tours for visiting media, diplomats and moguls.

I’ve seen the good and the bad, and only the bad gets into the newspapers and TV news. But in the global perspective all of that pales to the environmental impact of oil exploration in third world countries. Baku, Azerbaijan comes to mind. A Chinese drill rig in Sudan. A rusted and listing drill ship off the coast of West Africa.

Now don’t get me wrong — I don’t blindly support the oil industry. To me they’re like the Big Three Auto makers: auto-bots cranking out an inferior product nobody wants until one day…poof. It all ends.

Oil companies may be a bit more devious in their search for longevity, but just in case, I put a down payment on an awesome pure electric car — a Tesla Sedan — set for delivery in 2012. First time in my life I’ve planned that far ahead.

I actually had to prorogue my life for a few months to achieve that, my own personal re-calibration.

No, not really.

Mention the Seal Hunt and blood spurts out of people’s eyes, yet when I flew the Federal Fisheries people to inspect one of the last hunts in the 80s, I saw an orderly industry, well regulated and as humane as any abattoir. Of course I hunted and fished and trapped as a teenager growing up in the north, so I knew a thing or two about blood on the snow and the challenges of surviving off the proceeds of a trap line. Not easy.

Would I buy my wife a seal skin coat or shawl? Of course not. Fur just isn’t our thing.

So now I find myself in one of the world’s most dangerous places. And everyone in the world knows exactly how dangerous it is, because they see it on the news. And of course only ex-military, mercenaries, misfits and extreme adventure junkies go there. To fly helicopters.

So now I find myself in one of the world’s most dangerous places. And everyone in the world knows exactly how dangerous it is, because they see it on the news. And of course only ex-military, mercenaries, misfits and extreme adventure junkies go there. To fly helicopters.

Far from it.

I’ve never been in the military, nor would I wish enlistment upon my archenemy. Although I have gained some insight and moderation to those views…

No comment on the misfit category, but as for being an adventure junkie — up until a few years ago I couldn’t even climb a ladder to clean my rain gutters. Not because I had bad knees, or I just didn’t want to do such a mundane job. I simply suffered from an acute case of acrophobia — the fear of heights.

And how can a pilot be afraid of heights? Surprisingly, it’s not that unusual.

While researching an article on phobias, I learned that acrophobia affects 6 to 10 percent of the general population. But a retired professor of aviation psychology at the University of Southern California found that the rate of acrophobia was close to 90 percent in some of the pilot groups he studied.

Now that doesn’t mean that the next time you go flying you’re going to see the pilots break out in a sweat, or start chanting some Zen mantra to relax. That’s because pilots are in control of their environment, they understand aerodynamics and gravity, and some can even chew gum and walk at the same time.

I can take a helicopter to 10,000 feet and not bat an eye. I used to drop off geologists on narrow ridges and peaks, pick up drillers from tiny wooden platforms perched on the edge of a sheer cliff, and other than the normal anxiety experienced when confronted with the immense natural landscape, all was well in the universe.

But if I had to shut down on the sharp spine of a mountain range and wait for my customer, I would have to slide out of the helicopter, keep one hand on the machine, drop low to the ground — a Gollum-like creature dressed in a flight suit — and put on a great act of nonchalance. If I got too close to the edge, I could feel the gravity pulling me over and I frequently foresaw my tragic and ironic end.

Glass elevators, cable cars, suspension walkways, and peering over a high-rise balcony all produced the exact same sensation. Who needed an expensive roller coaster ride to get a thrill? Virtual rides with the seat moving all of one or two inches on hydraulic jacks was enough excitement for me.

Glass elevators, cable cars, suspension walkways, and peering over a high-rise balcony all produced the exact same sensation. Who needed an expensive roller coaster ride to get a thrill? Virtual rides with the seat moving all of one or two inches on hydraulic jacks was enough excitement for me.

The irony of this has been an endless source of disbelief and laughter — me being the brunt of most of it.

“You fly a helicopter but can’t go on a roller coaster?”

Yeah, yeah. I get it.

Then a few years ago I built an addition to our house, and I had to climb up and down ladders, scurry across joists and rafters — all in slow motion, mind you — one hand always in a death grip holding on for dear life. (The construction progressed in slow motion as well, a fact brought to my attention almost daily by my wife.) When it came time to finish the roof, I had myself tied off by ropes as if I were crossing a bottomless chasm on the ice fields of Mount Everest, even though I was, at most, eight feet off the ground.

But it worked — I faced that fear like some Charles Bronson character and was soon able to climb a ladder and knock the snow off our satellite dish. And last year I strapped on a harness, hooked myself up to a steel cable and zip-lined through the old growth forest of Vancouver Island. I even released my white-knuckle grip on the harness for a moment and enjoyed myself as I spun round and round, nearly out of control.

It’s all about risk management, and in the aviation industry I manage risk daily. On top of that, just to keep my licence, I have to write nine exams annually and subject myself to an annual Pilot Proficiency Check where every minute action and decision is evaluated while flying in a simulator. I have a medical every six months, where any minor blip on the doctor’s radar could mean the end of this particular career. If I had become a doctor or a lawyer I could have graduated and never be tested, prodded or evaluated again.

On the other hand, everyone in the aviation industry knows that flying is composed of hours and hours of boredom interspersed with moments of stark terror.

So maybe my bi-polar activity just comes with the territory.

Photo Credits

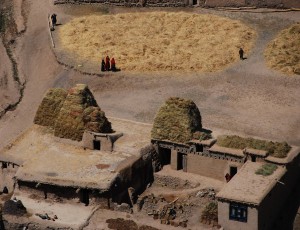

“Fieziabad” © Shawn Evans

“Winter Storage” © Shawn Evans

“Our Fleet” © Shawn Evans

Hi Allan,

Enjoyed your story very much. An insightful snapshot of the world through the eyes of a chopper pilot with a fear of heights. I too had a white-knuckled fear of flying for many years, until I realised that if I wanted to pursue my passion for travel writing and photography, I would just have to “get over it”.

If I had let my fear overcome me, I would have lived my life in South Australia, having deprived myself of meeting so many interesting people and seeing so many wonderful places around the world.

Regards,

Vincent Ross

P.S. I still like the sound of the tyres hitting the runway the best.