The café had not changed in decades. She and I ~ we had. We were past summer. I’m sixty-four, she sighed mixing cream into her decaf coffee.

The café had not changed in decades. She and I ~ we had. We were past summer. I’m sixty-four, she sighed mixing cream into her decaf coffee.

We sat across from each other in one of those German small town cafés which are dotted with round tables and comfortable chairs. People sat reading newspapers and eating apple cake with whipped cream. Waitresses, seemingly out of an earlier century in their black dresses and white aprons, attended efficiently. Paintings by a local painter cheered the walls with hearts in all shapes and colors.

I know, I told her. I’ll be sixty–three. I too sighed, relishing the last drops of latte, my second that afternoon.

Monika and I had known each other since we were from early childhood though we had not seen each other in over twenty years. I lived overseas and had not visited Germany in a long time. She didn’t use a computer, not even for email, so our contact had been reduced to one or two cards a year. When I made my plans to visit, I had felt a deep need to reconnect.

Her father had been a successful businessman, not a super-wow–millionaire, but he had made good money, just like my dad. They were friends and so Monika and I became friends. Monika is the youngest of three sisters; I am the oldest of three sisters.

Monika’s father left his family. His departure was not for another woman, actually. He lived as a bachelor for many years and remained a responsible father, but Monika just couldn’t accept losing her dad as part of her everyday life.

Getting together after our years apart, she relived those days. She repeatedly told me, “After he left, I cried every night. I felt abandoned. I felt a fatherless child and that seemed so much worse to me than if I’d been motherless! My sisters were older. They had boyfriends and seemed to be more able to let Dad go. But my world had broken into pieces.”

When she was fourteen and I thirteen, she fell in love with me. We lived in different cities, so she only visited during school vacations. In between, we wrote letters to each other every day.

She started going out with older men and, looking back now, the reason seems obvious. Monika was a young teenager; they were forty, even fifty. She knew her exploits impressed me. Yet, the reality wasn’t enough. Monika started to invent stories of men who forced her to drink or take drugs and to do all kinds of things you read about in the tabloids.

I believed her tales for a long time. When I finally realized that much of what she told me was made up, there was a crack in our friendship, but we survived that surprisingly.

Monika became her father’s secretary. She fell in love with a man who worked in the office, a younger man. After a while, she learnt he was gay. There were not many men after that, and it was about that time that she started getting sick. She suffered aches and pains, fainted or became debilitated by migraines. Had she not been the boss’s daughter, she would have been fired. Maybe her father understood that his daughter was sick because she was unhappy and that she was unhappy because he had left the family. Maybe he saw it as all his fault.

After many years her dad married again, a much younger woman. During his wife’s pregnancy, Monika had a stroke and was in rehab for a very long time. She decided she could not work anymore. Her father accepted that decision and paid her a pension.

When her half-brother was thirteen, their father died. Monika inherited his apartment, where she continues to live, receiving an income for life. The home is still filled with her father’s furniture and books, his paintings on the walls. Since his death she has become very close to my mother, her own mother having died a few years ago, nearly ninety.

Monika looks at me and says, “You’re so deep in thought.”

“I’m thinking about your life, “I answer truthfully. “You must feel very lonesome now.”

She sips at her coffee, which must have turned pretty cold.

“I haven’t had a relationship with a man for decades. I’m slim and I think not unattractive, but nothing happens anymore between men and me. I haven’t worked in ages either. In fact, I hardly go out. My legs are weak; I get palpitations and I cannot tolerate crowds. I tire easily. Just going to the supermarket exhausts me for the rest of the day. I don’t have any friends. I see my sisters and my nieces and nephews occasionally What do I do? Well, I read. I watch TV. I cook, but food doesn’t really interest me as it used to. When I have a good day, I take a walk. But see – it’s grey outside. These rainy days are actually a relief; they’re a good excuse not to leave the apartment.”

I simply don’t know how to reply. I rethink my own life with its ups and downs, years of depression and other health problems. There is the scepter of alcoholism and drug abuse in my family. But still, there’s so much movement, never a dull moment, journeys and exhibitions and many friends and the stories of my patients, still new projects all the time.

I simply don’t know how to reply. I rethink my own life with its ups and downs, years of depression and other health problems. There is the scepter of alcoholism and drug abuse in my family. But still, there’s so much movement, never a dull moment, journeys and exhibitions and many friends and the stories of my patients, still new projects all the time.

I look at my friend: the slender face, her grey hair, elegantly combed. All so very proper, all radiating infinite hopelessness.

“Once we die we’ll be dead for a very long time,” I finally reply, but what I want to do is take her frail shoulders in my hands and shake her. I feel like screaming,“Let it go.Let your miserable life go! Forget it. Pretend you have Alzheimer’s! It doesn’t matter. Just do something! Dance! Eat! Savour ten coffees, strong ones, but please, while they’re still hot! Come visit me. Fly across oceans or swim in one. Gaze at the stars!”

I know, though, that should I do that, she would burst into tears, dash from the café and bury herself in her father’s apartment for the rest of her life.

I have not hidden from life, not at all, but that has not kept me from screaming at myself, at the fates.I should follow my own advice. I too would do well to let go. I too must dance! swim! fly! gaze!

I think about the shoes I bought earlier today just before meeting Monika. They are absurd shoes for a woman my age. The flats are gilded with a huge flower shaped from the same fabric that covers the shoe. They are golden shoes, something my granddaughter would love to wear for her birthday parties.

“I’ll just wear them around the house,” I promised myself in the store, delighted they fit my wide, bunioned feet. I reach under the table for their bag, take them out and put them on the table in front of Monika.

My friend’s eyes have become clouded by endless days of rain, by the grey of northern Europe’s weather and the grey of her life. These fanciful shoes startle her. I watch her trying to understand my purchase. The flats are too large for a grandchild. Could they possibly be for me? Before she can voice a question, I order, “Put them on!”

I can feel her unspoken protest and so counter, “What do you have to lose?”

Monika takes the shoes and touches them tenderly, tracing their outline with her fingers . She dips down to remove her boring, safe, old lady’s black leather walking shoes, shoes worn by the elderly the world ‘round who wonder why their step is no longer light, where the spring in their gait has gone.

The flats are slipped on. We both bend down from our chairs toward her golden feet. Not only do they fit, but the shoes actually look better on her than they did on me. Monika peers up with a sheepish smile and then turns to face the patrons at the other tables. The older gentleman to her right has put his newspaper down and looks with us at the enchanting glow radiating from Monika’s feet. She and I meet his twinkling eyes at the same moment. He smiles, and I cannot believe what happens next: Monika blows him a kiss.

It is now early winter, dark outside and the rain has turned to light snow. “Let’s go,” I suggest, waving to the waitress to please bring the check. We’ve planned to stop at the nearby Christmas market.

Monika’s voice is as young as her shoes, “But I’ll leave the shoes on. Do you mind?”

On wet, wintry streets? The shoes will be ruined. Her feet will get soaked and tomorrow she’ll probably come down with a cold. “Of course,” I answer. ”Please wear them. But, hang on to me in case you slip.”

I pay and we put on our coats. I start to put her black shoes in the store bag, but she stops me. “I don’t need to keep those shoes,” she says in the firm voice of an elderly woman who knows what she wants, and what she doesn’t want. “I’ll just leave them here under the table.” And we do.

Entering the soft, magical aura which accompanies a softly falling snow backlit by street lights, Monika puts her arm tenderly through mine. Our hearts are as light as the drifting flakes, our steps as crisp as the air as we walk briskly towards the market.Who cares about tomorrow?

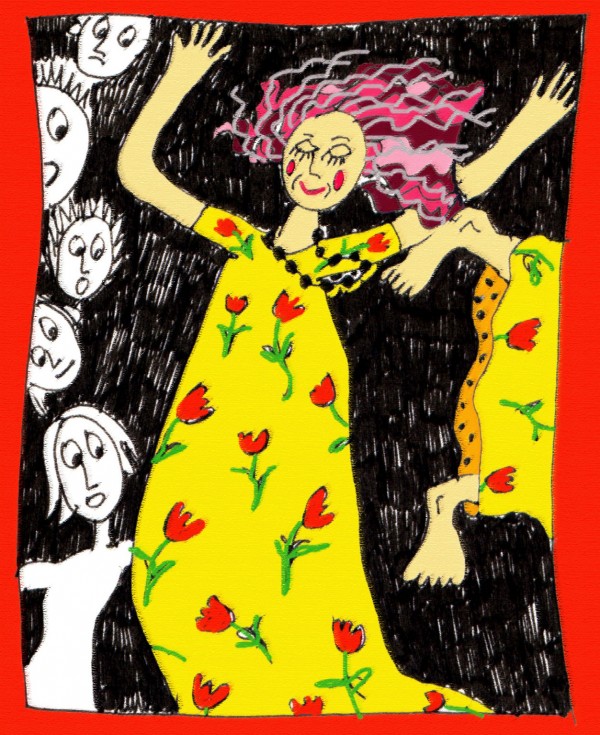

Image Credits

All Images Are © Kiki Suarez

Guest Author Bio

Kiki Suarez

I was born and raised in Hamburg, Germany. In 1977 as a young psychologist I emigrated to Mexico, where I married and had three sons. I am a painter and psychotherapist and work mainly with poor women and also teach Mindfulness Meditation. Together with my friend Gayle Walker I wrote the book EVERY WOMAN IS A WORLD, interviews with old women from Chiapas, published by University Of Texas Press in 2007. I run my own art – gallery and am going blind from a hereditary eye – illness – Retinitis Pigmentosa – which returns me to writing as much as I can. I live in the magic town of San Cristobal de Lasa Casas in Southeast Mexico surrounded by my sons and grandchildren, working hard at finding meaning in my life every single day.

I was born and raised in Hamburg, Germany. In 1977 as a young psychologist I emigrated to Mexico, where I married and had three sons. I am a painter and psychotherapist and work mainly with poor women and also teach Mindfulness Meditation. Together with my friend Gayle Walker I wrote the book EVERY WOMAN IS A WORLD, interviews with old women from Chiapas, published by University Of Texas Press in 2007. I run my own art – gallery and am going blind from a hereditary eye – illness – Retinitis Pigmentosa – which returns me to writing as much as I can. I live in the magic town of San Cristobal de Lasa Casas in Southeast Mexico surrounded by my sons and grandchildren, working hard at finding meaning in my life every single day.

Blog / Website: Kiki’s World – Kiki’s Welt

Recent Guest Author Articles:

- New Career and Degree Paths for Educators Who Want to Make a Broader Impact

- Exploring the World: How Travel Enriches Life

- Travel Smart: How Custom Screen Printed Shirts Can Enhance Your Brand

- Finding the Right Plumber in Portland: A Comprehensive Guide for Homeowners

- Why Choose Elara Caring for Jackson, MI Home Health Services?

Kiki, did Monika keep going with her newly found empowerment? It’s never too late:)

Dear Kiki…

Thank you for writing “your story” with Monika! I enjoyed reading it a lot, as I sit here in La Paz, B.C.S. I’ve been here for 4.5 mos doing volunteer work with charities involved in education of the niños and ninas of impoverished families in the Baja. It has been very fulfilling, and when I read you live in Chiapas and working with Mexican women, it made my heart sing…because, ANY work with the Mexican matriarchs will be invaluable for the culture. Bless you for your contribution! And continue to write, for as long as you can! I look forward to more of your writings. 🙂

Dear Monique, any work with any suffering human – being will change the future of this world or so I like to imagine….Much love to you in Baja California, if you ever come to Chiapas, call me, write me and we will chat and sip coffee or wine and make friends!

Kiki