Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Fukushima — the suffering goes on in Japan. Minimata disease, a neurological syndrome caused by severe mercury poisoning, was first diagnosed around 1956, and it is still claiming victims. Then the tsunami washed away thousands. It has been horrific for the population of those few over-populated islands which, according to legend, were created as an earthly paradise by the gods especially for the Japanese. It seems more like a living hell to me.

Cherry blossom season along the Tohoku coast, where disasters have kept many tourists away. Photo by Kozuki Ohahara for the NY Times.

Everything I know about Japan I learnt because of my Japanese penfriend. She never referred to Hiroshima or even Minimata in her letters. Obviously, with all the disasters raining down on that small group of islands I have been thinking of her, although we stopped communicating in the 60s when she left home to go to Tokyo University.

At the end of the 50s, the idea of Japanese penfriends was launched, I suppose, to repair international relations after the last war. Penfriends were the big thing. I had two French penfriends, an American penfriend from Texas, and one in Austria and another in Australia. You can imagine how beneficial these friends were for the development of understanding on a more international scale plus – we learnt to write well in our own language! We were not yet seduced by the promises of television so penfriends were a way of learning about the world and its ways.

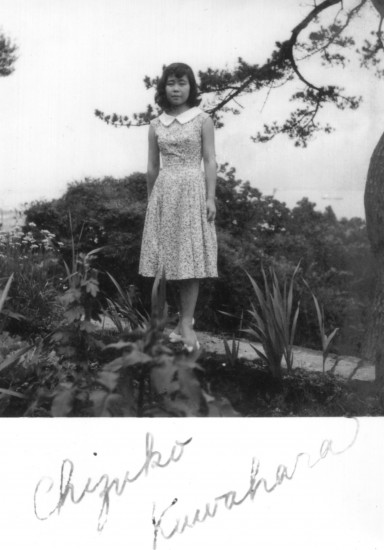

I was particularly fascinated by Chizuko Kuwahara, my Japanese penfriend, whose whole life style and system of beliefs were so far from anything I had encountered.

She lived with her family in Hokkaido the southern-most port on the North Island, just around the corner from where the earthquake and the tsunami hit and, more crucially, not far from the problem nuclear reactor.

Chizuko was a bit older than me, and her English was practically flawless, as my father kept pointing out! My family were all astonished at the quality of her handwriting (really good firm Copperplate) as opposed to my indecipherable scribble. Her written English was impeccable. She would diligently write to me about her life in Japan, her family, the festivals and her religion, which as a convinced Christian, I couldn’t begin, in my small mindedness, to comprehend.

I remember being slightly puzzled by the Japanese veneration of natural wonders like the cherry blossom. I hadn’t realised that for the Japanese, nature was an all-important part of their Shinto beliefs. It connected the Japanese to their land in a mystic way. For them, some parts of nature are considered to have an unusually sacred spirit about them, and these are objects of worship. They are frequently mountains, trees, unusual rocks, rivers, waterfalls, and other natural edifices. In most cases they are on or near a shrine.

The Japanese also have a shrine to their household gods. Although I don’t remember Chizuko telling me about a home shrine, I do remember that she described a day out in a local park where people put little paper boats in the water and watched them sail away downstream. This was at Obon, which is celebrated at different times throughout Japan depending on whether they are following a lunar or solar calendar. The festival was called Toro Nagashi, which means floating lanterns. Families send off their ancestors’ spirits in little paper boats lit with candles inside lanterns. They float out to the ocean and are thus liberated.

It is a Japanese Buddhist custom and has evolved into a family reunion holiday during which people return to ancestral family places and visit and clean their ancestors’ graves, and when the spirits of ancestors are supposed to revisit the household altars. This is like the French Toussaint (All Saints and All Souls) where family graves are cleaned and flowers set out and there is a big family get-together in memory of the departed.

My penpal sent me a special card with a lady in a kimono on it to tell me about the Japanese New Year’s holiday (January 1–3) which is marked by visiting Shinto shrines to pray for family blessings in the coming year, dressing in a kimono, hanging special decorations and eating noodles on New Year’s Eve. I remember her explanations, but I thought British Festive turkey was one up on noodles!

When she had no photos, she drew. I remember her pencil drawings of her house with its rice paper screens, futons that folded up into the wall, low tables and cushions for chairs. I thought they must be very poor.

She detailed her family’s visit to Fort Goryokaku local park to admire the cherry blossoms in May and explained some of the cold rice dishes they ate as a picnic under the trees. I was sure my Mum’s rice pudding was nicer! She sent me a huge collection of sepia postcards of all sorts of Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, the Emperor’s palace, and the little bridge leading to it and other important public buildings. In themselves, they didn’t encourage me to go to Japan, but as I got older I realised that there were many similarities between her world and mine.

Coming from Wales, I knew all about King Arthur and his knights, the Mabinogion stories and the Irish legends, so I was not at all surprised to find that the Medieval Japanese had their Samurai and a Bushido code. I began reading all sorts of old Japanese legends, learnt about the Geisha, and read novels and travel books about Japan . My chance came when my husband’s company sent him to Japan and I was allowed to accompany him.

I got hold of a book on how to speak Japanese (written in Roman letters) so I could learn all those useful phrases like Where is the hotel? Where is the toilet? What time does the train leave? Can I have two teas, please? Thank you for your help. Sorry. Excuse me. I don’t speak Japanese. We went several days earlier than his schedule of meetings so that we could stay in a Ryokan in Kyoto and could eat in choice restaurants. That is when I fell in love with Japanese food.

People were so impressed by my attempts at Japanese that I had a wonderful reception everywhere. As I was taller than most people, I could see over heads in the subways and people would come to offer advice even if I wasn’t lost. In the Ginza, the Japanese were so helpful and thoughtful, even drawing sketch maps to show me where to find a shop I wanted.

I realised after a few days that they were also like that with each other. The girls who bow down to you as you enter a big Japanese store, are showing you deference and welcoming you to the store but they do this for everyone. No one jostles nor pushes (except the station master trying to fit everyone in the subway!). The streets felt very safe although I was the obvious foreigner. It was one of the best holidays we had. Everything was so different but the Japanese made it so easy for us by their imperturbable natures and permanent gentle smiles.

My sister was so impressed by this holiday of mine that when her husband died and she wanted to assert her independence at 75, she went off to Oxford one day a week and learnt Japanese, and then spent a month in a school north of Tokyo. She now has a huge number of Japanese friends and has showered me with beautiful silk kimonos and obis.

I tried to re-contact Chizuko Kuwahara when I went to Japan but without any luck – this was before computers and Facebook. Although Chizuko would now be more than 75, she is probably still alive as the Japanese are amongst the longest living people on earth. There are 34.7 centenarians, in some parts of Japan, for every 100,000 inhabitants and that is the highest ratio in the world. Wikipedia says, in relation to Okinawa, “The possible explanation is the diet, low-stress lifestyle, caring community, activity, and spirituality of the inhabitants of the island.”

The Japanese have incorporated Buddhist beliefs into their daily lives so well that in addition to a respect for nature, their ancestors and their elders, they are capable of being very zen. This probably explains their incredible stiff upper lips in the face of all that life has thrown at them in the past few months. Television coverage hasn’t regaled us with scenes of wailing people shaking their fists at the gods or stretching out their hands in supplication.

Japanese spirituality and the Bushido code seem to have contributed to a certain national equanimity in the face of tragedy. Although the cardinal virtues of the Abrahamic religions are very similar, we Westerners no longer seem to face our tragedies with the quietness of spirit and intestinal fortitude of the long-suffering Japanese.

Photo Credits

All black and white photos courtesy of Julia McLean

Cherry blossom season along the Tohoku coast, where disasters have kept many tourists away. Photo by Kozuki Ohahara for the NY Times.

Please Share Your Thoughts - Leave A Comment!