The text is quite logical, outlining rational therapy for various orthopedic and neuro-surgical conditions in 48 concise case histories. What is more remarkable is that its author probably gathered most of his knowledge from the injuries of workers who built the Great Pyramids.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is the oldest surgical text in the world, most likely authored in the early portion of the third millennium BCE*. Egyptologist Edwin Smith purchased the papyrus in 1862 after it was discovered between the legs of a mummy from the Upper Egyptian necropolis of Thebes. No doubt a prized possession of the deceased owner, this version was transcribed during the 17th century BCE with a “modern” commentary after each case.

The papyrus was translated by Prof. J. Breasted in 1930 with the help of a physician colleague, and the now-famous text finally ended up in the collection of the New York Academy of Sciences. Any modern physician will find the unknown author’s format quite familiar with sections devoted to history and physical examination, followed by a diagnosis, prognosis and treatment plan.

Though ancient Egypt’s priests often had medical training there is no evidence in this text of the prayers and amulets that often were used by this class. Instead our anonymous surgeon laid out elegant and simple diagnostic and treatment programs some paralleling those of modern medicine almost exactly.

For example in case 12 “A Break in the Nasal Bones” treatment is described as follows: “Thou shouldst force it to fall in, so it is lying in place, and clean our for him the interior of both his nostrils with two swabs of linen until every worm (clot) of blood which coagulates in the inside of his two nostrils comes forth. Now afterward Thou shouldst place two plugs of linen saturated with greases and put into his nostrils. Thou shouldst place for him two stiff rolls of linen, bound on. Thou shouldst treat him afterward with grease, honey and lint every day until he recovers.”

In other words the nose is set, clot evacuated and splints of stiffened linen are applied. Non-stick grease soaked dressings are used to pack the nose. This is much the same approach an ear nose and throat specialist would use today.

In case 35, “A Fracture of the Clavicle (collar bone)”, treatment of a patient is described as: “Thou shouldst place him prostrate on back, with something folded between his two shoulder blades; thou shouldst spread out with his two shoulders in order to stretch apart his collar bone until the break falls into place. Thou shouldst make for him two splints of linen, and thou shouldst apply one of them both on the inside of his upper arm. Thou shouldst bind it…”

In other words draw the shoulder blades back and fit the patient with “figure of eight” splint, exactly what a modern orthopedics text would advise.

The 21st (ACE**) intern confronted with a dislocated jaw need look no further than case 25 of the Edwin Smith Papyrus. “If thou examinest a man having a dislocation in his mandible, shouldst thou find this mouth open and his mouth cannot close for him, thou shouldst put thy thumbs upon the ends of the two rami of the mandible in the inside of his mouth and thy two claws (meaning two groups of fingers) under his chin, and thou shouldst cause them to fall back so they rest in their places.” This is exactly the technique I learned in the ER!

In many cases the treatment was beyond the capability of the time and the surgeon simply states that this is “…an ailment not to be treated”, i.e. a very poor prognosis. Nevertheless he meticulously describes the physical findings of such injuries as in case 31 “Dislocation of a Cervical Vertebra (neck bones)” where he writes if “…thou find him unconscious of his two arms and his two legs on account of it, while his phallus is erected…, and urine dribbles from his member without him knowing it…; it is a dislocation of a vertebra of the neck extending to his back-bone …”. This is the world’s first known description of quadriplegia, neck-down paralysis like that from which Christopher Reeve suffers.

In case 6, “A Gaping Wound in the Head With Compound Comminuted Fracture of the Skull and Rupture of the Meningeal Membranes”, we get the first description the brain and its gyri (convolutions or folds), and the meninges (the tough outer coating of the brain).

“If thou examinest a man having a gaping wound in his head, penetrating to the bone, smashing his skull, and rending open the brain…, thou shouldst palpate (feel) that smash which is in his skull like those corrugations (i.e. folds) which form in molten copper, and something therein throbbing a fluttering under the fingers…” The pulsation of the brain is described and later the author observes that its absence is a very serious sign (which indeed it is, representing serious brain compression).

In case eight “Compound Comminuted Fracture of the Skull Displaying No Visible External Injury”, the ancient surgeon articulately describes hemiplegia, or paralysis on one side secondary to a head injury: “Shouldst thou find that there is a swelling protruding…, while his eye is askew because of it (conjugate deviation of the eyes), on the side of him having that injury which is in his skull; and he walks shuffling with his sole on the side of him having that injury which is in his skull.”

The author further states: “Thou shouldst account him one whom something entering from outside has smitten…” It appears here that he may be trying to differentiate hemiplegia caused by an “outside” injury as opposed to similar findings which may occur from an “inside” cause such as a stroke.

In other parts of the text the ancient surgeon describes suturing lacerations, and treatment of infection and wounds with non-stick dressings and hyperosmotic agents (animal grease and honey respectively). In case 39 it is suggested that an abscess which “…arises in his breast dries up as soon as it opens of itself.” In other words as my old surgery prof said, “Pus under pressure should be punctured”.

The text appears to differentiate breast tumors as opposed to infections, describing the former in case 45 “Bulging Tumors on the Breast” as “…very cool, there being no fever at all therein when thy hand touches them; they have no granulation, they form no fluid, they do not generate secretions of fluid, and they are bulging to thy hand.” Is this the first description of a breast cancer?

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is only one of a number of remarkable Egyptian Medical texts discovered. Almost as famous is the The Ebers Papyrus also first purchased by Edwin Smith and subsequently sold to Egyptologist George Ebers, for whom it is named.

It is 110 pages in length, the longest discovered. It is to family doctors what the Smith Papyrus is to surgeons. In addition to a surgical section it contains descriptions of the heart and its vessels, discussions of various diseases such as those of the stomach, anus teeth, ear nose and throat, and skin. Skin diseases are divided into ulcerative, irritative and exfoliative similar to modern dermatology classifications. A section on pharmacy includes various treatments including the use of castor oil as a laxative. There’s even a section on medical philosophy.

Another papyrus, the Kahun Gynecological Papyrus deals with diseases of women and dates from the 19th century BCE. It contains sections on topics such as contraception and the diagnosis of pregnancy.

It’s easy to see why the Egyptians were revered in the ancient world for their medical knowledge. It boggles the mind to think that these texts pre-date the Roman Empire by as many millennia as Rome pre-dates us. To Egyptians, even Hippocrates was a mere upstart. The ancient Egyptian physicians at their best show a logical and surprisingly up-to-date approach to the diagnosis, classification and treatment of disease. Perhaps “modern” medical thought is not as modern as we once thought.

*Before Current Era or Before Common Era.

**After Common Era

Photo Credits

All photos by George Burden

Author on camel-back at Giza with Great Pyramids in background

Medical instruments on display at Coptic Museum in Cairo

Medical instruments depicted on the walls of the Temple of Komombo

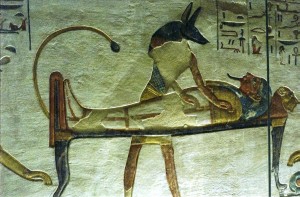

Ancient Egyptian embalming ritual

[…] Read more about ancient Egyptian medicine in George Burden’s previous Life As A Human article, “‘Doc’ Like an Egyptian.” […]