By now, the rhetorical question – “Who am I to judge?” – posed by Pope Francis in an impromptu scrum with reporters on the flight back to Italy from Brazil following the activities of World Youth Day, has found its way into countless discussions, both public and private, of this pontiff’s attitude towards homosexuality and his view of the teachings of the Church on the subject. The pope was responding to the question of how he would deal with a (sexually inactive) gay clergyperson in his circle, and his full answer was “Who am I to judge a gay person of goodwill who seeks the Lord? You can’t marginalize these people.”

By now, the rhetorical question – “Who am I to judge?” – posed by Pope Francis in an impromptu scrum with reporters on the flight back to Italy from Brazil following the activities of World Youth Day, has found its way into countless discussions, both public and private, of this pontiff’s attitude towards homosexuality and his view of the teachings of the Church on the subject. The pope was responding to the question of how he would deal with a (sexually inactive) gay clergyperson in his circle, and his full answer was “Who am I to judge a gay person of goodwill who seeks the Lord? You can’t marginalize these people.”

The speculation on whether this statement – and others made by the pope since then – signalled a sea change in how the Catholic Church treats homosexuality and LGBTQ persons has been endless and loud. Francis himself claims that as “a son of the Church” he cannot and does not wish to change its doctrine, but he has also made it clear that he wishes the Church both to take a more merciful attitude to those who have been marginalized in the past and to shift its energies away from policing doctrinal orthodoxy and in the direction of reaching out with love – to all humans, not just heterosexual, obedient Catholics.

But it is difficult for the Church, as it is for other churches and other religions, not to judge when much of its doctrine is based on judgment. An insistence on moral absolutism implies that the one insisting possesses the wisdom, the knowledge, and the authority necessary to determine what is right and what is wrong, who is right and who is wrong on every moral issue. Perhaps Francis is seeking to soften this insistence and the often harsh judgments resulting from it; to this Holy Father, it appears, moral absolutism must be tempered with mercy and love.

Meanwhile, in spite of Francis’s apparent encouragement of a more reasonable and more pastoral approach, the Catholic Church in the United States continues to marshal its moral and financial resources, at the front lines of the culture wars, in fierce opposition to the legal enfranchisement of gay rights in that country (while their Canadian Excellencies lost the battle many years ago). However, losses in recent skirmishes – the Supreme Court overturning DOMA and effectively burying California’s Proposition 8; the legalization of same-sex marriage in an increasing number of states through popular vote or legislation; courts in other states declaring illegal constitutional amendments affirming marriage as only between one man and one woman – may be signalling that a more conciliatory approach is not too far down the road. The pope’s often stated requirement that the names of more pastoral clergypersons be put forward for possible appointment to the office of bishop may speed this process.

Perhaps because the Holy Father is a Jesuit himself, the Jesuits in the U.S. have made the first formal public gesture of any substance in bringing the two sides of this issue, as it is being played out in the Church, closer together. Moral philosopher and Georgetown University professor John P. Langan, S.J. has written a thoughtful and very carefully worded piece, entitled “See the Person,” in the Jesuit journal America. In his article Father Langan attempts first to “read [Francis’s] words and actions and offer suggestions about how to construe them so that they form a coherent picture.” Langan believes that the pope, while unwilling (and perhaps unable) to change or reverse doctrine, is attempting to modify the Church’s stance on homosexuality to one that is “more discerning, more compassionate.” The author implies that the pope’s public rethinking of the issue stems both from who he is and from the fact that the “traditional view [of the Church on homosexuality] is now widely regarded as vulnerable, embarrassing and unpersuasive.”

Father Langan suggests that “four important elements should mark a new stance toward homosexuals and homosexuality.” These are humility (both sides must acknowledge what they don’t know); “respect for the dignity of homosexual persons”; acknowledgement of “the problems of perception and trust that complicate our efforts to understand and collaborate with one another”; and patience on all sides.

The conclusion to the article is that there must indeed be a change in the way that the Church treats LGBTQ persons; the “principal change would not be in the teaching of the church on the moral acceptability of homosexual activity, but in affirming and practicing pastoral ministry for persons engaged in irregular or questionable unions.”

It is refreshing and encouraging to witness the courage of a member of the clergy of the Catholic Church in suggesting in a public forum that the stance of his Church on the issue of homosexuality is in need of change. Moreover, Father Langan has clearly laboured painstakingly to present a balanced view of the problem, to mitigate the intransigence, the anger, and the hostility that has characterized this argument and to raise it to the level of a dialogue marked by respect and open-mindedness. Many will see his article as a significant step toward a meeting of Catholic hearts and minds on a delicate topic.

I am afraid that I am not one of the many. First, if Father Langan and others hope that his essay will become the basis for a broader discussion of bringing the Church and Catholic LGBTQ persons closer together, they must first understand that the exclusive use of the word “homosexual” to refer to gay people is going to be an obstacle to fruitful dialogue; anyone who has even marginally followed the gay rights movement over the past 45 years is aware that the term “homosexual” reflects the view that being gay is a disorder and that it will be taken by the vast majority of gay people as both ignorant and insulting.

Father Langan’s article also demonstrates a lack of understanding of the LGBTQ community when he uses terms such as “gay and lesbian agendas,” “alternative lifestyles” and “personal choice” in reference to sexual orientation, and “irregular and questionable unions” in reference to gay relationships. It is common knowledge in contemporary life that being gay is not an alternative lifestyle, unless marginalization constitutes an alternative lifestyle; in fact, as Langan himself acknowledges, more and more LGBTQ people are choosing so-called traditional lifestyles by marrying their partners, raising children, and buying homes in suburbia. And it is even more ludicrous to refer to being gay as a personal choice. Who would consciously choose to be closeted or ridiculed or bullied or rejected by their families and their church?

The most fundamental flaw in Father Langan’s approach lies in what he so valiantly attempts to accomplish: to validate the arguments of each side. While it is admirable on the surface, the problem with this approach is that validating the argument of the traditionalist side automatically invalidates that of the LGBTQ side. What if we were to say to left-handers: “We know that we have treated you badly in the past and that it might be wrong for us to force you to use your right hand, so we are going to offer you more compassion and greater pastoral care. Nevertheless, we still think that you are disordered and we are pretty sure that we should not approve of using the left hand.” The tone and language of Father Langan’s article will lead just about every gay person who reads it to believe this is exactly what he is saying about him or her.

A teaching, a tradition, a doctrine, even a stance is a construct, albeit often a complex one. None of these is a human being created in the image of God. An LGBTQ person is just such a human being, and science has shown that he or she is in no way disordered, unless marginalization, rejection, or demonization has disordered that person. An LGBTQ person is equal in every way – in intelligence, in creativity, in holiness, in the ability to love and in the need to be loved – to a straight person. Any theology, any religious teaching that places this community in the category of “other” is not only flawed; it is immoral.

If Pope Francis is telling the Church through his words and through the example of his behaviour that the first duty of the faithful is to set aside judgment in favour of the practice of unconditional love, there is hope that the Catholic LGBTQ community will find a home in the Church. While Father Langan’s essay reflects deep thought and careful consideration of a sensitive issue, it does not reflect an understanding and appreciation of gay people as whole human beings, which is a necessary starting point, in my view, of accepting us as full members of the Church.

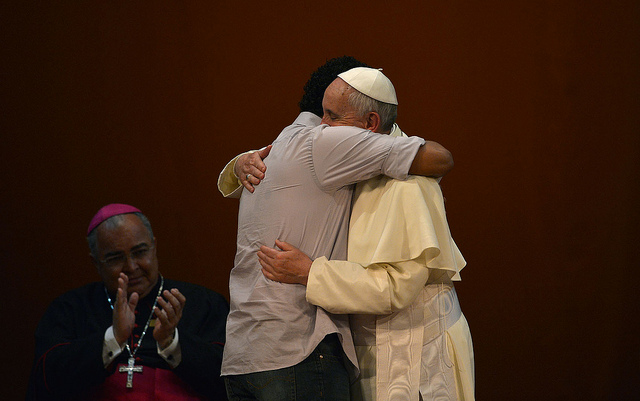

Image Credit

“Visita Papa Brasil” by Semilla Luz. Creative Commons Flickr. Some rights reserved.

Recent Ross Lonergan Articles:

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Four

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Three

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Two

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part One

- Bullying, Fear, And The Full Moon (Part Four)

Please Share Your Thoughts - Leave A Comment!