Walking across a windswept parking on a bone-chilling, dark February night I had time to reflect on a movie and a former professor of mine who was indirectly associated with it. I had just seen George Clooney’s recent release “The Monuments Men”, a film with a great story to tell but its screenplay is weak and acting mediocre. The film is loosely based on Robert Edsel’s meticulously researched, well-written book of the same name. The book’s subtitle frames the movie and book well, “Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, And the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History” and Professor Theodore Heinrich, a great educator, was a part of this.

Walking across a windswept parking on a bone-chilling, dark February night I had time to reflect on a movie and a former professor of mine who was indirectly associated with it. I had just seen George Clooney’s recent release “The Monuments Men”, a film with a great story to tell but its screenplay is weak and acting mediocre. The film is loosely based on Robert Edsel’s meticulously researched, well-written book of the same name. The book’s subtitle frames the movie and book well, “Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, And the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History” and Professor Theodore Heinrich, a great educator, was a part of this.

Clooney’s movie begins in 1943 and ends during May 1945 as the Second World War in Europe draws to a close. But the story of The Monuments Men who worked for the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFA&A) section of the Western Allies (America, Britain, Canada) doesn’t end there, it continues until 1951. It’s the post war period from 1945 to 1950 that Professor Heinrich, as I came to know him, worked with MFA&A.

I first met Professor Heinrich in the mid-1970s as an undergraduate student at Toronto’s York University. A well-spoken, dapper individual of the highest intellect, he was an engaging professor. He was passionate about preserving and promoting humanity’s cultural treasures.

I first met Professor Heinrich in the mid-1970s as an undergraduate student at Toronto’s York University. A well-spoken, dapper individual of the highest intellect, he was an engaging professor. He was passionate about preserving and promoting humanity’s cultural treasures.

Professor Heinrich taught a museology class (the study of museums) which captivated me as I had an interest in history and archaeology. Almost immediately we got along extremely well so I was given the honour of a private viewing of his incredible collection of European documents, drawings and books, some going back to the 1500s.

Taking time out after class one afternoon I rendezvoused with Professor Heinrich at his office. Our conversation drifted from museology to a reminiscence of his life. He told me that his family had wealth and that he had grown up in California where he attended university. What struck me was how restless he was in his youth. His desire to travel was overwhelming so he struck off to Europe travelling around the continent relishing in its rich cultural inheritance of art and architecture.

As the afternoon continued on he began talking about his years in England at Cambridge University, which he entered during the early 1930s and where he earned his master’s degree in architectural history. He spoke of his years at Cambridge fondly and he told me that during the Second World War he had worked on General Dwight Eisenhower’s staff. This took me by surprise; I’d never met anyone who had worked at such a high level during the Second World War. Growing up immediately after the war all of my friends had father’s who had served as soldiers, just as my own father had, but all at the lower rungs of military hierarchy.

As the afternoon continued on he began talking about his years in England at Cambridge University, which he entered during the early 1930s and where he earned his master’s degree in architectural history. He spoke of his years at Cambridge fondly and he told me that during the Second World War he had worked on General Dwight Eisenhower’s staff. This took me by surprise; I’d never met anyone who had worked at such a high level during the Second World War. Growing up immediately after the war all of my friends had father’s who had served as soldiers, just as my own father had, but all at the lower rungs of military hierarchy.

I listened intently as he told me how he’d worked in the intelligence branch at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) in England. The section Professor Heinrich was assigned to gathered intelligence on railway systems in Germany, Belgium, Holland and France which were used by the German armed forces. This was incredibly important work since it provided the Canadian, British and American air forces with the railroad targets to bomb which effectively destroyed the rail network needed to support the German war effort.

The NAZIS hid stolen art in over 1,000 locations across Germany and Austria so as the first wave of Monuments Men were returning home during mid-1945, a new group came onto the scene. It would take years to find several million pieces of stolen artwork and other historic artefacts of cultural value. With his background in art history it made sense to transfer Professor Heinrich to MFA&A at war’s end.

He went on to tell me that he was posted to Wiesbaden, Germany which became the MFA&A collection point for German-owned art. It was in Wiesbaden where he and other Monuments Men identified and returned German art to the institutions and private individuals who originally owned them. By 1947 he became the director of the Wiesbaden collection center.

He went on to tell me that he was posted to Wiesbaden, Germany which became the MFA&A collection point for German-owned art. It was in Wiesbaden where he and other Monuments Men identified and returned German art to the institutions and private individuals who originally owned them. By 1947 he became the director of the Wiesbaden collection center.

I sat there in silent amazement as Professor Heinrich talked about rebuilding German museums and in the process recovering works by Renoir, da Vinci and other great masters. Not your typical academic. Of the 30 professors I had while attending university, both at York and later at the University of Toronto, he was one of the few who had made a lasting impression.

In 1981, while working on an archaeological dig in Kingston,Ontario, I called Professor Heinrich at his home in Toronto. He hadn’t immediately recognized my voice, which I thought was rather odd as we had always enjoyed many conversations over the years. Moments later a woman came on the line to tell me that Theodore was gravely ill. He passed away a short time later.

Photo Credits

Photo 1. Theodore Heinrich, shown in his U.S. Army uniform about 1945, was an art expert and real life Monuments Man

who ended up teaching at the University of Regina in 1964-65. (University of Regina archives)

Photo 2. Theodore Heinrich, in light-coloured civilian dress, is shown receiving art at a depository for recovered lost or stolen art

run by the U.S. Army. The photo was taken around 1949 in Wiesbaden, Germany. (University of Regina archives)

Photo 3. Heinrich (right) and an unidentified colleague examine what in 1949 was believed to be one of the most valuable paintings

in the world, Rembrandt’s Man With A Golden Helmet. It was hidden in a salt mine before being recovered by the Americans.

In 1985, it was reclassified as painting done by a student of Rembrandt’s. (University of Regina archives)

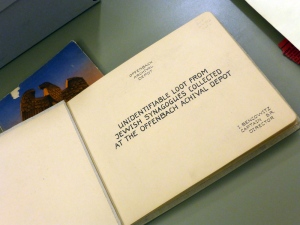

Photo 4. Title page from a catalogue owned by Heinrich of looted Jewish art objects:

Unidentifiable Loot from Jewish Synagogues Collected at the Offenbach Archival Depot. (Sean Prpick/CBC)

I was in two of Professor Heinrich’s art history classes in the mid 70’s. I was his “slide girl” during his lectures. When he needed a slide changed, he would snap his fingers. I remember him saying that he couldn’t afford to fix his teeth because he was always buying art and art history books. I hope I remember this correctly; I think he mentioned that after the war, he was looking for the Nefertite bust, which he found wrapped up where it was left, in the Berlin Museum (?) He was very happy to have her see the light of day again.

At the end of the year, he held a “do” for his fourth year seminar students, in his flat in Rosedale. The apartment was covered in paintings ; from Rembrandt etchings to a rather large Hogarth on the back of a door. There were literally towers of books everywhere. Some older ladies came in greeting someone. “Hello Ted”, they said. I realised they were referring to professor Heinrich.

I think about him from time to time. Today, for some reason, I decided to do a google search. I didn’t know he had passed away, too soon, only a few years after I graduated from York. I knew it was a privilege to be in his classes. He was someone who was awesome in the true sense of the word. Thank-you for this article.

I was also one of Professor Heinrich’s museology students for 2 years at York University during the late 1970’s. His influence was amazing. I look around my home which is covered floor to ceiling with artwork that was denounced by the Nazi and Stalinist regimes. I was lucky to start collecting at such a young age. I frequently think of how privileged I was to have the rare opportunity of studying with such an individual.

Dear Marai, Theodore was a great professor. His style of teaching challenged his students intellectually. I’m not aware of any books published regarding his life although he did publish materials on his research. Most of the material I located on him was through the University of Regina archives and to a lesser extent through the Monuments Men Foundation, York University, the Royal Ontario Museum, Concordia University and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Cheers, Joseph.

Sir Theodore Heinrich most amazing man. he was my professor at York University in the late 70s. I assisted him teaching Egyptian Art history. I left Toronto in 1980 to continue my studies in Florence and upon my return in spring 1981 a friend came over to tell me that he had passed away. He had always asked about my wherabouts. And this is what I regret the most not having ever called him to explain what i was studying. Today, I still talk about him about his Studies and the research he’s done . He taught through his experiences in the art world. Today not all professors teach the way he did. Has anyone written a book about him? Where can i find what he has written ? I’m glad i found your article. A 100 times Thank you. Regards MCandida