I have used the term “courtroom drama” for this article because it appears to be a popular or standard term for movies centering on a legal case, but after viewing numerous films I found that much of the drama in these stories often takes place outside the courtroom – in introducing the characters and their involvement in the case, in depicting the process of investigating the circumstances of the case, in dramatizing the preparation of the legal arguments, and so on. Sometimes only a small portion of the film is actually devoted to courtroom scenes, and in the case of one great “courtroom drama” with which I am familiar, the entire film is set in the jury room. Perhaps a better title might be “legal drama,” but I bow to convention and use the preferred term.

A courtroom is an ideal setting for the dramatic playing out of conflict between two sides of an issue, the heart of all compelling stories. Brilliant and eloquent attorneys, each cleverly manipulating the facts and circumstances of the case to advance his or her argument; hostile, vulnerable, or cunning witnesses adding to the mystery or stunning the court – and the audience – with surprise testimony; a stern, witty, or biased judge who maintains the balance of the scales of justice or tips them in one direction or the other – these elements and more, percolating in a closed room, combine to make the courtroom drama one of the most exciting genres on the big screen.

Who can forget Atticus Finch’s passionate plea to a bigoted jury for justice for Tom Robinson in To Kill A Mockingbird. Or the explosive courtroom exchange between naval lawyer Lt. Daniel Kaffee and Marine Colonel Nathan Jessup in A Few Good Men (This film is a masterful piece of writing by the inimitable Aaron Sorkin and it is well directed by Rob Reiner; it would have appeared on my top-five list, but, unfortunately, I did not find either of the leads, Tom Cruise and Demi Moore, to be credible in their roles). Or Captain Queeg’s unforgettable breakdown, brilliantly rendered by Humphrey Bogart, under the interrogation of Navy defense lawyer Lt. Barney Greenwald (José Ferrer) in The Caine Mutiny.

And while it was not set in a courtroom and there was no judge and no prosecutor or defense attorney present, the struggles and confrontations of the twelve men in the jury room made Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men a memorable “courtroom drama.”

Here are five of my favourite classic films in this genre.

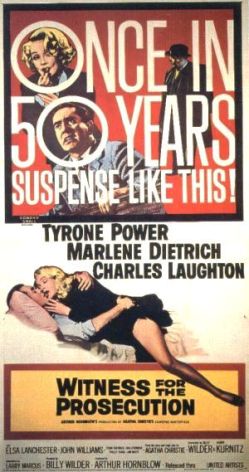

#5 – Witness for the Prosecution. (Directed by Billy Wilder, starring Tyrone Power, Marlene Dietrich, and Charles Laughton, 1957). This is a finely rendered cinematic version of the Agatha Christie short story and play, in which the performances of Dietrich and Laughton shine brightly. Laughton is a barrister under sentence of death by heart failure if he does not refuse all criminal cases and rest under the care of the overbearing and tirelessly loquacious Nurse Plimsoll (played by the delightful Elsa Lanchester). But he cannot refuse the tantalizing case of Leonard Vole, who is accused of murdering a wealthy widow. Lots of twists and turns and exciting courtroom fireworks keep this rather light-weight film moving along. My favourite scene is Laughton’s cross-examination of Vole’s wife, played by Dietrich, in which he asks her, in his inimitable voice, “…and are you not in fact a chronic and habitual LIAR!”

#5 – Witness for the Prosecution. (Directed by Billy Wilder, starring Tyrone Power, Marlene Dietrich, and Charles Laughton, 1957). This is a finely rendered cinematic version of the Agatha Christie short story and play, in which the performances of Dietrich and Laughton shine brightly. Laughton is a barrister under sentence of death by heart failure if he does not refuse all criminal cases and rest under the care of the overbearing and tirelessly loquacious Nurse Plimsoll (played by the delightful Elsa Lanchester). But he cannot refuse the tantalizing case of Leonard Vole, who is accused of murdering a wealthy widow. Lots of twists and turns and exciting courtroom fireworks keep this rather light-weight film moving along. My favourite scene is Laughton’s cross-examination of Vole’s wife, played by Dietrich, in which he asks her, in his inimitable voice, “…and are you not in fact a chronic and habitual LIAR!”

#4 – Reversal of Fortune. (Directed by Barbet Schroeder, starring Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close, and Ron Silver, 1990). There is very little interesting courtroom “action” in this film; the drama occurs outside the ring, in the events and family dynamics leading to the charges against Claus Von Bülow, the decision of idealistic law professor Alan Dershowitz to take the case, the relationship between Von Bülow and his lawyer (and thus between truth and lies, between idealism and ego), and the preparation of the case. Ron Silver is brilliant as Dershowitz; Jeremy Irons is in fine form as the cool and enigmatic Von Bülow.

#4 – Reversal of Fortune. (Directed by Barbet Schroeder, starring Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close, and Ron Silver, 1990). There is very little interesting courtroom “action” in this film; the drama occurs outside the ring, in the events and family dynamics leading to the charges against Claus Von Bülow, the decision of idealistic law professor Alan Dershowitz to take the case, the relationship between Von Bülow and his lawyer (and thus between truth and lies, between idealism and ego), and the preparation of the case. Ron Silver is brilliant as Dershowitz; Jeremy Irons is in fine form as the cool and enigmatic Von Bülow.

#3 – Inherit The Wind. (Directed by Stanley Kramer, starring Spencer Tracy, Fredric March, and Gene Kelly, 1960). The names have been changed, but this is clearly a dramatization of the famous Scopes Monkey Trial, in which a young Tennessee teacher is accused of breaking the state law that prohibits the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution. March plays the prosecuting attorney Matthew Harrison Brady (aka three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan), a bible-thumping but brilliant orator; Tracy is defense attorney Henry Drummond (aka Clarence Darrow). The meat of the film is the passionate conflict, enacted in the courtroom of a small Southern town, between literal belief in the Bible and scientific rationalism, a conflict played out against a background of ignorance and bigotry. March and Tracy are the entire movie here; their electrifying performances stand in contrast to the 1950s Hollywood-plastic crowd scenes in the town, along with the wooden portrayals of the secondary characters (except for Gene Kelly, who is excellent as a cynical Baltimore newspaper man).

#3 – Inherit The Wind. (Directed by Stanley Kramer, starring Spencer Tracy, Fredric March, and Gene Kelly, 1960). The names have been changed, but this is clearly a dramatization of the famous Scopes Monkey Trial, in which a young Tennessee teacher is accused of breaking the state law that prohibits the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution. March plays the prosecuting attorney Matthew Harrison Brady (aka three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan), a bible-thumping but brilliant orator; Tracy is defense attorney Henry Drummond (aka Clarence Darrow). The meat of the film is the passionate conflict, enacted in the courtroom of a small Southern town, between literal belief in the Bible and scientific rationalism, a conflict played out against a background of ignorance and bigotry. March and Tracy are the entire movie here; their electrifying performances stand in contrast to the 1950s Hollywood-plastic crowd scenes in the town, along with the wooden portrayals of the secondary characters (except for Gene Kelly, who is excellent as a cynical Baltimore newspaper man).

#2 – Twelve Angry Men. Please see my Life As A Human review of this film.

#1 – Judgment at Nuremberg. (Directed by Stanley Kramer, starring Spencer Tracy, Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, Marlene Dietrich, Judy Garland, Maximilian Schell, and Montgomery Clift, 1961). This film is outstanding in every aspect. It is 1948. The Nazi leaders have taken their own lives, fled, or been tried and executed; only minor officials who collaborated with those leaders or perpetrated atrocities remain to be dealt with. The American people are tired of the war and public as well as official attention is now being drawn toward the dawning Cold War, a conflict in which German support is seen as crucial. It is in this environment that the trial of four German judges, including the distinguished Ernst Janning (Lancaster), takes place in the infamous city of Nuremberg. The excellent screenplay, written by Abby Mann, is sensitive in its handling of several questions: Were the German people as a whole responsible for the crimes carried out by the Third Reich? Do duty and loyalty to one’s country excuse one from guilt for offenses committed against individuals and groups considered “dangerous” to the state? Do political exigencies trump the notion of justice?

#1 – Judgment at Nuremberg. (Directed by Stanley Kramer, starring Spencer Tracy, Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, Marlene Dietrich, Judy Garland, Maximilian Schell, and Montgomery Clift, 1961). This film is outstanding in every aspect. It is 1948. The Nazi leaders have taken their own lives, fled, or been tried and executed; only minor officials who collaborated with those leaders or perpetrated atrocities remain to be dealt with. The American people are tired of the war and public as well as official attention is now being drawn toward the dawning Cold War, a conflict in which German support is seen as crucial. It is in this environment that the trial of four German judges, including the distinguished Ernst Janning (Lancaster), takes place in the infamous city of Nuremberg. The excellent screenplay, written by Abby Mann, is sensitive in its handling of several questions: Were the German people as a whole responsible for the crimes carried out by the Third Reich? Do duty and loyalty to one’s country excuse one from guilt for offenses committed against individuals and groups considered “dangerous” to the state? Do political exigencies trump the notion of justice?

There are some marvellous performances in the movie: Maximilian Schell as the lawyer appointed to defend the four judges, brilliantly and subtly personifying some of the important themes of the movie; Lancaster as Janning, maintaining great dignity while admitting terrible guilt; and Montgomery Clift as Rudolf Petersen, the slow-witted son of a communist railroad worker, who was sterilized under Janning’s order. Tracy is perfect as the lower-court American judge appointed to oversee the trial and pass judgment on the defendants; he is at once humble and self-assured, compassionate and damning, all the while maintaining an air of countrified simplicity.

At over three hours, this movie is riveting from beginning to end.

~

In each of these films, it is the legal case that is the centre of the drama; naturally, as legal cases – at least those that are worthy of being made into films – involve people, these are human dramas as well. Honourable mentions in this category include A Cry in the Dark, Anatomy of a Murder, Erin Brockavich, The Verdict, and Philadelphia.

In other films, such as To Kill A Mockingbird, mentioned above, the legal issues and courtroom drama do not play a central role; they exist for the purpose of supporting the expression of a larger theme.

I am certain that there are many good films in this genre that I have failed to mention and that others have opinions regarding which courtroom dramas should be included in a “top five” list. I am happy to give all of these films and all of these critics their day in court.

Image Credits

“Witness for the Prosecution Poster” Wikipedia

“Reversal of Fortune Poster” Wikipedia

“Inherit the Wind Poster” Wikipedia

“Judgment at Nuremberg Poster” Wikipedia

Recent Ross Lonergan Articles:

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Four

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Three

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Two

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part One

- Bullying, Fear, And The Full Moon (Part Four)

Interesting article and well articulated, but I do not agree on all your choices. I would say Cry in the Dark is a better film then Inherit. the wind. I found the trial in the latter film rather like an episode from the Andy Griffith show then a serious, tense and anguished story about a man on trial for his beliefs. I kept expecting someone to say golly gee wiz. The tension and drama in cry in the Dark never let up. Each actor played their role perfectly. The story moved quickly and held my attention throughout. In both movies there was a religious zealot, but in Cry in Dark, the zealot went through a serious crisis of doubt which was entirely believable given the horrific nightmare that he was forced to endure. The zealot in Inherit the Wind never relented, never questioned his beliefs, never doubted which made him seem almost two dimensional at times.

Hi Susan:

Thank you for your thoughtful comments. I agree that A Cry in the Dark is an excellent film, and I would definitely have included it in my top five, but in the end I felt that the movie was less about the legal case than about the investigation of the “crime,” about the reaction of the Australian public to the controversy, and about how the couple were affected by the incident and its aftermath.

As for Inherit the Wind, I have to disagree with your Andy Griffith analogy. As I have a great deal to say about this (and will perhaps have more to say once I finish reading Spencer Tracy’s biography), we will carry on this argument at the dinner table.