Westminster Abbey, a Benedictine monastery and Catholic seminary in Mission B.C., had been on my mind for some months before I contacted the Guestmaster and made arrangements for a three-day retreat at the end of February. I am writing a novel that is partly set in a monastery—the protagonist is a young seminarian and, much later in the story, a Benedictine monk—so I wanted to get a feel for monastic life and for the setting of this abbey. What’s more, I was a seminarian there for a very brief period in 1964 and had not been back since; I was curious to see how the abbey had changed—and how it may have stayed the same. Finally, I simply felt the need to be in a peaceful place for a few days, without duties or responsibilities, to purge a negativity that had been steadily growing in my mind like a tumour. Despite these “expectations,” I actually had no idea what the experience would be like and wanted to be open to whatever form my retreat might assume.

Westminster Abbey, a Benedictine monastery and Catholic seminary in Mission B.C., had been on my mind for some months before I contacted the Guestmaster and made arrangements for a three-day retreat at the end of February. I am writing a novel that is partly set in a monastery—the protagonist is a young seminarian and, much later in the story, a Benedictine monk—so I wanted to get a feel for monastic life and for the setting of this abbey. What’s more, I was a seminarian there for a very brief period in 1964 and had not been back since; I was curious to see how the abbey had changed—and how it may have stayed the same. Finally, I simply felt the need to be in a peaceful place for a few days, without duties or responsibilities, to purge a negativity that had been steadily growing in my mind like a tumour. Despite these “expectations,” I actually had no idea what the experience would be like and wanted to be open to whatever form my retreat might assume.

The Benedictine order was established in honour of Saint Benedict of Nursia, who lived in the sixth century. The order follows the Rule of St. Benedict, a set of precepts governing monastic life laid down by Benedict toward the end of his life. Rule 53 states: “Let all guests who arrive be received as Christ, because He will say: ‘I was a stranger and you took Me in’ (Mt 25:35). And let due honor be shown to all, especially to those ‘of the household of the faith’ (Gal 6:10) and to wayfarers.” In my communication with the abbey’s Guestmaster (who, to my great astonishment, remembered me from nearly fifty years earlier) I learned that the maximum length of stay permitted by the abbey was three nights. I would thus be getting a glimpse of monastic life rather than a true feel for it, but I happily accepted the condition and booked my stay.

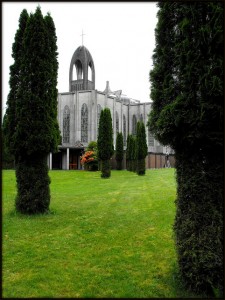

I arrived at the monastery on Wednesday afternoon, the last day of February, after a ninety-minute trip along unfamiliar roads in the ubiquitous rain of the Fraser Valley, miraculously turning at exactly all the correct intersections. The rain turned to snow just as I entered the abbey driveway and by the time I got to my room the beautiful and extensive monastery grounds that slope down from the guesthouse toward the Fraser River were covered in a blanket of white. Unfortunately the snow ultimately turned to a cold rain that lasted for the remainder of my visit.

The motto that governs the lives of Benedictines is ora et labora, work and pray. Thus the monks (of which there are about thirty, ranging in age from early twenties to early nineties) and the senior seminarians pray in the abbey church four times daily (in addition to hours of private prayer); there is also a sung Mass every morning at 6:30. On that Wednesday afternoon, I attended Vespers, the most elaborate, and to my heart and my ear, the most hauntingly exquisite of the prayers. The antiphonal chanting of the psalms fills the church with a kind of benignly masculine sound that is at once enchantingly medieval and thrillingly in the moment, a moment that is enriched by the excellent acoustics of this unusual and impressive building. For the rest of my visit I attended all the prayers, including Lauds at 5:05 AM; on my last day I even joined in the chanting, if somewhat tentatively and quietly.

The motto that governs the lives of Benedictines is ora et labora, work and pray. Thus the monks (of which there are about thirty, ranging in age from early twenties to early nineties) and the senior seminarians pray in the abbey church four times daily (in addition to hours of private prayer); there is also a sung Mass every morning at 6:30. On that Wednesday afternoon, I attended Vespers, the most elaborate, and to my heart and my ear, the most hauntingly exquisite of the prayers. The antiphonal chanting of the psalms fills the church with a kind of benignly masculine sound that is at once enchantingly medieval and thrillingly in the moment, a moment that is enriched by the excellent acoustics of this unusual and impressive building. For the rest of my visit I attended all the prayers, including Lauds at 5:05 AM; on my last day I even joined in the chanting, if somewhat tentatively and quietly.

The abbey’s guesthouse is busiest on weekends when large groups come for retreats; for the first twenty-four hours of my visit there was only one other guest and on the evening of the second day, four Anglicans arrived for a short retreat. Individual retreatants and small groups like the Anglicans take their noonday meal and their supper with the monks in the refectory, a large high-ceilinged room that used to be the abbey church. This was an experience I had not anticipated and which I found fascinating.

Rule 53 also states: “On no account shall anyone who is not so ordered associate or converse with guests. But if he should meet them or see them, let him greet them humbly, as we have said, ask their blessing and pass on, saying that he is not allowed to converse with a guest.” I do not believe that this part of the rule is strictly observed today, but there is still very little opportunity for protracted contact with any of the monks other than the Guestmaster and those who are charged with assisting in the guesthouse. Certainly the monastery building itself is off-limits to guests. Thus it was a privilege to be given the opportunity to be with the monks in a slightly less formal setting than public prayer and Mass.

In the short time since my retreat ended I have been wondering why I found eating with the monks to be perhaps the most interesting and memorable aspect of my visit. I suppose it is because observing them in this setting allows us to see them both as monks and as human beings just like those of us who live in the “dusty world.” Monastic meals do have their strictures, the rule of silence being what we of the secular world might consider the most demanding, but there is something about the act of eating that touchingly humanizes these men, reflecting their individuality and exploding the image of monk as pious cipher.

If I harboured any stereotypical preconceptions about monks, they were quickly swept away by the Guestmaster, a man whose wry humour, solicitousness, and knowledge of the world would make him a welcome neighbour. At breakfast one morning (these meals were not taken with the monks but in the dining room of the guesthouse), he was an active and interested participant in a conversation that ranged from the Stanley Cup riots to homosexuality and ephebophilia. The following day our breakfast companion was the celebrant of that morning’s Mass, a priest who happened to have been rector of the minor seminary when I was a student in 1964 (in fact, it was likely he who called my parents and suggested that I was not ready for seminary life and should be taken home) and is now approaching 85 years of age. As sharp as any knife in my mother’s kitchen, he charmed and entertained us throughout the entire meal and then graciously took his leave as he pushed the cart full of dirty dishes back to the kitchen.

If I harboured any stereotypical preconceptions about monks, they were quickly swept away by the Guestmaster, a man whose wry humour, solicitousness, and knowledge of the world would make him a welcome neighbour. At breakfast one morning (these meals were not taken with the monks but in the dining room of the guesthouse), he was an active and interested participant in a conversation that ranged from the Stanley Cup riots to homosexuality and ephebophilia. The following day our breakfast companion was the celebrant of that morning’s Mass, a priest who happened to have been rector of the minor seminary when I was a student in 1964 (in fact, it was likely he who called my parents and suggested that I was not ready for seminary life and should be taken home) and is now approaching 85 years of age. As sharp as any knife in my mother’s kitchen, he charmed and entertained us throughout the entire meal and then graciously took his leave as he pushed the cart full of dirty dishes back to the kitchen.

In the company of these two men it was easy to forget that they have lived lives of chastity, poverty, and obedience, of prayer and work, in this small community for at least fifty years. Whatever sacrifice such a life once entailed, though, appears to have long since been transmuted into a sense of peace and joy that, while tempered indeed with traces of ego and with the daily irritations of life, radiates from them with a gentle luminosity rarely encountered in men of the secular world.

As for the many hours I spent alone in my cell (actually a simple but very nice room, with a large, private bathroom), they were almost entirely taken up, after an evening and a morning of “spiritual” reading, by an unexpected yet utterly satisfying journey into William Styron’s flawed but achingly beautiful and passionate novel, Sophie’s Choice. The discovery of this work and the lessons it offered to me as a writer were a gift that the quiet hours of this retreat allowed me to receive and to appreciate and that deepened my commitment to my own humble vocation, doubly treasured for the very lateness of its arrival.

A rewarding three days indeed, for which I am deeply grateful.

Photo Credits:

Westminster Abbey by new_sox

Backside by iBjorn

inside church #9595 by Nemo’s Great Uncle

Recent Ross Lonergan Articles:

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Four

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Three

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Two

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part One

- Bullying, Fear, And The Full Moon (Part Four)

Ross,

I agree that Sophie’s Choice is an exquisite and profoundly moving novel. However, I was amazed that it was that book which you chose to take with you on a contemplative retreat. For me it would jar the serenity of the experience.However, I’m sure you had your definitive reasons for taking it.

Anne: Indeed the content of Sophie’s Choice is jarring – shocking, actually. And I can understand why it might seem out of place at a monastic retreat. But I had read the novel before and had seen the movie several times, so this time I was able to focus on the beauty of the language. And it was only one of a large number of books I took as I was headed to my mother’s following the retreat and I always take plenty to read on my monthly visit to her place.

Moreover, the retreat was not as “comtemplative” – at least in the traditional sense – as I had expected it would be. There were simply too many new, and old, impressions for me to process in that short stay for there to be space for quiet contemplation. I am sure that the next visit and subsequent stays will be different.

Thanks for your comment.

I loved it. But you’ve left me with a desire to read (hanging, really) a Part 2 of this lovely article. Do tell-how your stay impacted “purging a negativity that had been steadily growing in my mind like a tumour.”

Thanks for your comment, Kaycee. This was actually quite a difficult article to write because there were so many impressions over the three days that it was a challenge to organize them into some kind of coherent whole. Thus I am not sure that I would be able to write a Part 2; perhaps I will do that after my second visit, which I plan to make this fall. As for purging the negativity, I made no conscious effort to do so, but I suppose it was naturally replaced with the positive “vibes” of the abbey and of Styron’s gorgeous novel.

A lovely piece

Thank you.