Steven Erikson takes on a controversial and often painful subject — themes. How do writers approach themes honestly, in a way that is true to the story, without driving a personal agenda?

Ignoring this sense of backing into a corner, I have decided to write about theme. This is dangerous territory, one in which a good many of my opinions and thoughts on the subject are likely to irritate if not infuriate some of my readers (and those fellow writers who happen to look in). Well, it’s not like I have anything to lose, all things considered.

I generally begin a story with an idea of what it’s about. I might think this story is about heroism, or grief, or siblings, or motherhood. I might think this is about feeling lost in the world, or the search for meaning/love/God/hope/faith. Or I might think this series will be about the struggle of all of the above. What I don’t think is this: that this story is about how stupid and useless left-leaning liberals are, or how only gun-toting Republican Americans can defeat the alien hordes, or that you can be a good Waffen SS as long as you don’t hate Jews … and still defeat the alien hordes.

If you think I just made up those story ideas, you haven’t read John Ringo and friends.

A theme is not a position, not a political slant, not an agenda, just as a work of honest fiction is not propaganda, polemic, or didactic diatribe. What theme is, among other things, is an area of exploration. And ‘exploration’ is a journey into the unknown, one that breaks down and discards preconceived notions. Exploration involves courage and determination, often verging on the obsessive; as many historical accounts of past explorers will attest. Your enemy is the unknown; your fear is the unknowable, and the peace that follows – if it follows – only comes when the fear goes away. Note that I do not mention wisdom, since as far as I can tell wisdom is another word for world-weary exhaustion, and every wise word uttered is born from bitter experience, and upon hearing such words, one chooses to either take heed or not. Accordingly, bitter experience breeds anew with every generation.

I recall that in creative writing classes, people were often afraid to tackle theme, as a subject for discussion, or as a point of contention. It seemed to be held as somehow sacred, forever ephemeral, not to be approached in the same profane manner as one approaches point-of-view, or dialogue, or sentence pattern. Those few of you reading here who knew me in my workshop days, may (or may not) recall the numerous occasions when I got rather rabid on issues of theme in someone’s story. It’s like reading a landscape: it helps to know the underlying geology that gives it shape, and if no-one else is prepared to wield a pick, well, I am. Why? Because I use that same pick on my own shit, that’s why.

I recall one very well-written story by a fellow student. The tale was set on a farm and involved a wife abandoned by her husband. There were, I recall, a couple other male characters in the tale as well, and each and every one of these men were reprehensible, portrayed with open venom. The story climaxed (and I use the word deliberately) in a scene where the main character takes a cleaver to a turkey’s neck on a chopping block, aptly describing said neck as looking like a flaccid penis. Now, don’t get me wrong: it was a great story, technically, and she was and no doubt remains an excellent writer. But it was false. It was a world created by a blinkered god (the author). Not all men are pricks. Maybe 97 percent of them are, but not all. What I was witness to, then, was the author’s agenda, and that agenda, no matter how truthfully arrived at through personal experience or whatever, became a suspect manipulator of truths, and its fuel was bitter anger.

Who sees clearly when bitter and angry? There was no exploration here: it was a hack at old ground, one over which the author paced back and forth as if caged by the world.

And I suppose she was. Caged. But the story didn’t rattle the bars, didn’t look for a way out, had no time at all to even think about escape. It liked where it was, even as it hated it.

I have (I think) written about ruthlessness before, the force that must be turned not only upon a work of fiction (or art in general) but also upon oneself: upon one’s own most cherished beliefs. If I haven’t, well, there it is. Agendas that survive their iteration in fiction are, to my mind, evidence of failure; specifically, the author’s failure. They wrote how they want it to be, not how it is.

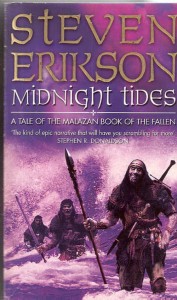

This brings me, at long last, to my portrayal of the Empire of Lether starting in the fifth novel in the Malazan sequence, Midnight Tides. The reason this subject is on my mind is that, once again, I have been asked in a Q&A whether that empire and its political and economic system was intended as a commentary on the United States. Each time I am asked this question, my response is no. So, let’s take this as definitive: there were two major themes in that novel, the first being about siblings and the journeys made by two sets of three brothers, and the second being about inequity.

This brings me, at long last, to my portrayal of the Empire of Lether starting in the fifth novel in the Malazan sequence, Midnight Tides. The reason this subject is on my mind is that, once again, I have been asked in a Q&A whether that empire and its political and economic system was intended as a commentary on the United States. Each time I am asked this question, my response is no. So, let’s take this as definitive: there were two major themes in that novel, the first being about siblings and the journeys made by two sets of three brothers, and the second being about inequity.

It’s likely that one would have to go back to the Paleolithic to find a human society not structured by inequity, and even that is debatable, given the social characteristics of our nearest relatives, chimpanzees and gorillas. Without question, the agricultural revolution early on, which established sedentary civilizations, went hand-in-hand with the creation of a ruling elite and an emerging class system. The crust needs sludge to sit on, and the more sludge there is, the loftier the crust. Maintaining this system is made easier by inculcating the notion that the best rises to the top, and that opportunities always exist for it to do just that, although one could argue that these latter notions are more recent manifestations – certainly, the slave or serf in antiquity would need to step outside of the law to achieve wealth and comfort (and it’s no accident that such laws are both created by, maintained, and enforced by the elites).

I set out to explore inequity (as an aside, I have travelled through socialist countries and fascist countries, and guess what, shit smells like shit no matter what flag you stick it in), and one thing Midnight Tides taught me was that once a certain system of human behaviour become entrenched, it acquires a power and will of its own, against which no single individual stands a chance. A rather dispiriting conclusion, I admit. To this day, I’d love to see proof to the contrary.

I did not know I would reach such conclusions – well, not so much ‘conclusions’ as grim observations, and I wasn’t particularly pleased to find myself where I did.

Every social construct now in existence among humans is founded upon inequity of some sort. People of one political persuasion or world-view will tell you it’s some kind of natural order, and thereby justify whatever cold-heartedness they harbour; others on the opposite end will decry the evidence and call for a leveling of humanity devoid of individuals. Both have had their day in history, and any particular pitch at present is, as far as I can see, a minor blip on the screen. We’re nothing if not headlong.

Themes. Themes can hurt. They can cut deep inside. There’s a reason why the subject is often taboo in writing workshops. Stripping back the façade can reveal unpleasant things.

And the next time someone asks me if the Empire of Lether was a direct riff on the United States, I will say no, and mean it.

Dubious writing tip #7; subject: theme: Find out what you want to write about. Choose key words and stack them in your head, leaving them to do a slow-burn through the writing of your story. Don’t look at the light, don’t fan the flames, don’t flinch when they burn. Write around the fire, circling, ever circling, working to edge closer as the story progresses. Drive for the moment when you get singed, scorched. Then pull back, smarting. Study the red welt. Good enough? If it hurts like hell … probably good enough.

Heal. Start again.

Cheers,

SE

Photo Credit

“Alchemist Killing Hamlet” h.koppdelaney @ Flickr.com. Creative Commons. Some Rights Reserved.

Recent Steven Erikson Articles:

- Deconstructing Fiction (For Writers and Readers): Excerpt Deconstructed (8)

- Deconstructing Fiction (For Writers and Readers): Excerpt Deconstructed (7)

- Deconstructing Fiction (For Writers and Readers): Excerpt Deconstructed (6)

- Deconstructing Fiction (For Writers and Readers): Excerpt Deconstructed (5)

- Deconstructing Fiction (For Writers and Readers): Excerpt Deconstructed (4)

Steve is right in saying this has been a fascinating conversation!

I have found myself in the same situation as Paul. I’ve had this huge desire to write, but I’ve been having problems in a few of the topics you’ve hit upon in your blog series here. So first of, Mr. Erikson, let me say thank you for the time you’ve invested in these articles and commentaries.

The discourse between everyone so far has been very enriching about why some books fall flat even though they appear mechanically sound on the surface.

The issue of Theme, though, has always left me wanting. While trying to extrapolate working in the theme from other authors hasn’t been as satisfying as the salient points you highlight in your post were missing. It’s like trying to figure out the ingredients after a cake has been baked. Further clarifying these points in the comments was like the icing on the cake.

The proselytization of a theme has turned me off many good books and has been my primary complaint behind what happens to (an otherwise great) author’s final few books. I found this in the likes of Goodkind (his first few books had me riveted) to J.K. Rowling, among others. So your warning to other authors regarding the danger is, in my opinion, well founded.

But what I truly love is the fact that you take the time explain the “why” and you really hit the nail on the head.

I live over on the Mainland and, if you still give them, would love to take one of your seminars.

The rub is, I’m currently working in Ethiopia. (Your novels kept my sanity when I was stuck in Uganda and a friend lent me the first book.) I would be interested if you ever put your seminars on a podcast or pen them to a book.

Anyway, keep up the posts – you have at least 1 eager audience member following with rapt attention.

-T-

That post nicely reframes my perspective on the original article – I can see now (I think) that we were discussing two different kinds of certainty; one in a very broad sense, the other in a more focused, story-centered sense.

And with regard to story, there is nothing I can find here to disagree with. As a student of medieval lit., I found myself wanting to take issue with the statement that “didactic writing destroys story”. But on reflection, the writers of morality plays and other literature of a partially or wholly didactic nature were themselves not primarily concerned with “story” anyway, at least as we understand the term. And what I find valuable or interesting in such works is indeed not their narrative so much as other qualities (theological/philosophical explorations and constructs; technique; patterns of motif). Incidentally, this is probably why it’s near impossible to do justice to a piece like Beowulf in film; accommodating the poem to modern expectations of narrative does a good deal of violence to the “atmosphere” etc. of the original. (For my money, The 13th Warrior is the best “adaptation” I’ve seen.)

At any rate, in the context of story craft, all of the above statements (especially regarding the dangers of oversimplification/shortcuts) allow me to see the original post in some new light; thanks for that.

Paul

So here a fascinating conversation has been going on — damn, wish I’d looked in sooner. As a final comment on the above, there is the risk of reading too much into a writer’s take on why they write as they do: overriding all of this, in terms of motivation, is the desire to tell a good story. So let’s go back to my earlier statement about didactic, polemical writing and its implicit ‘danger.’ I was being careless. I am not applying some ethical blanket over such lumpy stuff, as if to apply a value judgement on the content itself. When I spoke of ‘danger’ I meant it in term of ‘story.’ In other words, didactic writing destroys story, just as the author’s convictions, if held fanatically and unquestioningly, will destroy story. It does so because it lacks tolerance and understanding of contrary or disparate points of view or belief systems. And it is doomed to do unless and until the author swallows down some humility and dispenses with certainty. The point here is the ‘story’ is paramount. My personal life and its moral compass is actually not even relevant to any of this, and I fear some of you have conflated your sense of that compass (as derived from my fiction) with my argument against certainty in fiction.

Story needs to reflect the complexities of the human condition. If it cheats, if it takes shortcuts (with cut-out bad guys, etc), then it fails in honestly reaching for a sense of that human condition. This is not in itself a political or even an ethical position (though with the latter, I invite you read John Gardner’s thoughts of Moral Fiction). Rather, it is a question of craft.

Cheers

SE

Good post Steve. I shall refer people who ask about the Lether/US tie here–I’ve seen the same question. It has puzzled me as Midnight Tides and Lether didn’t seem to me to be about the US at all. It was, as you say, an exploration in inequity (and the brother journeys). History is strewn with examples of inequity. The particulars of how the inequity manifests are different, but it always comes out. It doesn’t usually end well (never to date?) . And then it starts over again.

“What I don’t think is this: that this story is about how stupid and useless left-leaning liberals are, or how only gun-toting Republican Americans can defeat the alien hordes, or that you can be a good Waffen SS as long as you don’t hate Jews … and still defeat the alien hordes.

If you think I just made up those story ideas, you haven’t read John Ringo and friends.

A theme is not a position, not a political slant, not an agenda, just as a work of honest fiction is not propaganda, polemic, or didactic diatribe.”

Got to admit, I haven’t read John Ringo, but this seems like a cheap shot.

I see in the Malaz books (and I’m not finished a first reading yet; roughly halfway through Bonehunters) all kinds of characters who lose faith, have no faith, believe in nothing. Those who *do* believe in a cause – political, religious, or otherwise – are the “dangerous” ones. It’s such a pronounced tendency in the books that I sometimes have difficulty remembering or determining the characters’ motives at all, beyond immediate survival or vengeance.

The series has a pervasive “agnostic” (and pessimistic about society/history) tang to it – nothing wrong with that, but it strikes me as in fact the sort of thing you rail about in the above paragraphs: If the messages I imagine I find in your books seem to match the attitudes you express in your blog, isn’t that just another version of an author ultimately controlling the message of the work?

Is it because Ringo’s politics seem so obviously silly and parochial that his books are fair game for the accusation of polemic and propaganda?

I’m not saying there are tracts of diatribe littered throughout the Malaz series (I wouldn’t keep reading if there were, and I am a big fan of the books), but there are points that seem less like exploration and more like depiction of an authorial worldview, one that could be said to have its own “agenda”.

There’s no way around this, I guess, as we all have our biases. As we explore ideas, we make discoveries and naturally want to put those into words, share them with others, knock them against other worldviews. But my question here, I suppose, is, when does exploration turn into proselytizing? And how much can (or should) a writer resist that turn?

Interesting questions, Mr. England. Was that a cheap shot? Read Ringo and come back to me on that one (my descriptions are accurate). When exploration reaches proselytizing all exploration has ceased. If you sense an agnostic take on things in the series, bear in mind that agnosticism is about uncertainty. If your sense pessimism in the series, read on, because the struggle in this series concerns just that. Fiction is about crisis: that crisis can be external (and externalized) and most adventure-based stories lean heavily on that side, and offer up as counterpart heroes for whom crisis plays little or no role in their internal world-views. By extension, an author whose world-view is some immutable force, impervious to doubt, remains to my mind both dangerous and deluded. What I am seeking to explore in my fiction is stories where both character and events are at crisis points, inasmuch as the external world and the internal world are in constant dialogue. In a general sense you could say that is why the heroes are flawed: everyone is in crisis. Some are honest with it, some aren’t; some are aware of it and others have convinced themselves that they’re just fine. Take a step back from the story, and you have the author. I suppose what I am speaking for is writing with some kind of humility, combined with (dare I say it) embracing crisis. And why bother? Well, I think it’s about finding compassion (not a bleak, pessimistic or nihilistic conclusion) and then seeing where that takes me.

cheers

SE

Thank you for taking the time to reply. (After looking through some of his books on Amazon, I’m not about to sign up for the John Ringo fan club.)

You’re right that exploration and proselytizing cannot be the same thing. What I was trying to say is that explorers are often impelled to share the discoveries resulting from their explorations. How does a writer do that without falling into the “trap” of certainty? Is it even possible to do so? A belief that certainty – an immutable worldview – is dangerous is itself a kind of worldview, and a kind of certainty, it seems to me.

The discussion about exploration has me thinking about planning. I have assumed from early on that the Malazan series was plotted out in some detail well in advance. If that was in fact the case, how did you find yourself able to act as an explorer of those crisis points – internal and external – without already knowing where you were headed?

That question has a particular urgency for me, as I find myself at the beginning of an increasingly overwhelming project, working on a first book of my own. I seem to be craving certainty for myself (just where is this thing *going*?!), but also aware that too much of it can be the death of the work. How do you balance the inclination to have a certain mastery over your story with the desire for it to burst free of the restraints such control would thereby impose?

I imagine the answer is different for every writer (if they consider the question at all). Still, as someone who is right now reading (& much enjoying) your series, I’d be interested in your take.

-Paul

Hi Paul

Sorry, should have looked in on this a few days back! With respect to your project and approaching particular scenes while bearing in mind the internal and external exploration … one way is to throw at least two points of view at the same event or situation, and playing them off each other; or to follow on with multiple interpretations of said event. The key here is to believe each and every interpretation you convey through each character; that is, to believe it as they would, up to and including being prepared to fight from that position if it comes to that. For me, what’s valuable in this is also what tends to prove most humbling, as those divergent and often conflicting points of view all have validity. By this means, writing is a process, and stays a process (rather than a regimented, sterile recitation), and writing itself becomes a thing of exploration.

Thank you for that suggestion – most helpful!

I’m still thinking through it, but I can see how I may have been approaching narrative as primarily a sequence of events – when in fact the events that occur in the fictional world occur only at one “level”. The other level, implied by your response, is that of the interpretation of the characters. So, while I may know what will happen, roughly, in the story, there is still considerable leeway in the approach(es) the characters themselves take.

That leeway, I take it – and the ability/willingness of the writer to allow for such leeway – is the arena of exploration.

This is a very helpful model of the process, allowing for planning as well as creative commitment to characters… It’s something I will definitely be thinking about as I proceed (and looking to see how other authors work it).

Thanks again!

Paul

What about “proselytizing” in order to do exploration together, wherever it takes? 😉

Not a chance, Ab. Proselytizing starts from a foundation of unquestioned and not-to-challenged assumptions. Exploration demands openness, all senses engaged and ready for input; at which point the writer becomes observer as much as does the reader.

Heh, as soon as I read that paragraph I knew who he was talking about because I *have* repeatedly read John Ringo & friends. I describe their work as kind of the male equivalent of Mills & Boon – they involve alpha male types fulfilling all the great stereotypes – big explosions, hot girls, everything larger than life. They tend to be brash, in-your-face style works where good guys triumph, and the bad guys get whut comes to em. Ringo himself is unashamed about just how bad some of his works are, he considers them guilty pleasures and was amazed that anyone else would want to buy them.

And they definitely have a place, as cheerful popcorn style reading, much in the same way as Michael Bay makes popcorn style movies – you would never go see Transformers for the plot, you see it to watch giant robots bashing each other senseless as stuff blows up around them.

Unfortunately for Ringo, or more applicably for some of his co-writers when they branch out on their own, their underlying cultural preferences sometimes take over their work.

For example Tom Kratman made for a great co-writer in the cheesy Waffen SS one mentioned above, but his solo work I found extremely difficult to read because the entire story was slanted in favour of a severe right wing worldview, one that I find highly disagreeable, with blatant strawman opponents set up for the heroes to knock down. Now, one of the worst things a reader can do is to treat the worldview of a character as that of an author, but when an in-book universe is created, it is created with certain underlying assumptions, and as said above the author needs to be careful that those assumptions do not tip the line between more subtle suggestion and blatant proselytizing.

I’ve read works where the agenda is left wing, and others where it is right wing, I guess the simplistic philosophy of right wing america is just more in fashion at the moment, as opposed to say the left wing propaganda from the seventies counterculture.

One of the great things about the Malazan series is the breadth of world SE has managed to create, and how while in one book you get one side of a story, sooner or later you see or hear about particular events from different angles, whether from other characters, or as rumours, or as fragments of a historical record. It is that depth that truly reflects reality in all its glorious misconceptions that really attracts me to the series.

Oh, and looking back at our own history, the most frightening characters that crop up from time to time are those that truly believe in something. And the scary part is just how far they are prepared to go for that belief. Fortunately they have been less common than people think.

Then does it follow that the most admirable characters that crop up are those who don’t believe in anything?

Or is it simply that the worldview of admirable characters – their own set of beliefs – more closely matches our own?

The belief that belief is bad is a belief. A wholesale indictment of strongly-held beliefs, I fear, may simply give us a way to avoid talking precisely about what we find objectionable; it may become easier to say that belief itself is the problem, not the particular ideologies or actions.

It seems to me that most actions, good or bad, are predicated upon belief. We may despise the tyrants of our day, observing how they propagate and manipulate belief. But when we admire those who rebel against them, I think we admire their actions and self-sacrifice, both of which have their origin in belief (unless they are simply reflexes).

According to my ever-receding memory of college philosophy classes, without belief there can be no knowledge – and, I would suggest (as no doubt others have before), no humanity either.

Whether humanity, knowledge, and thus belief are worthy of celebration as opposed to regret is, of course, a different question.

Interesting thoughts.

In my mind, belief per se is not an admirable trait. It is a motivator, possibly the most powerful one after emotions, but not in itself something pro or ante.

True belief in something, whether a cause, or something greater, or even just in what one person is capable of has led people to do extraordinary things, from Mawson to Joan of Arc, but equally it is not common – the stories of triumph through adversity are held up as marvels simply because the number that gave up and failed are so much greater that the few particularly stand out.

I find the ability to stick to your beliefs through whatever may assail them to be frightening because in my mind it means the person has closed their minds to alternatives, good or bad. It is that refusal to countenance other options that is labelled as steadfast, faithful and resolute, or intolerant, dogmatic and bigoted. Which way it is seen depends on who is doing the seeing, is the person a Tyrant, or a Leader, a Martyr, or a Deluded Fool.

In literature, admiration comes from how the characters are written, and generally develops over time as the characters evolve. It is less particular traits as how they embody those traits, and what they do with them that matters. A well written antagonist can often be extremely admirable even as they thwart the hero purely because their character is acting in a justified manner. Goldfinger for example, is admirable because he treats Bond with respect, in full knowledge of what he is capable of, and gives him no easy means of escape. The whole mass murder theft thing is a bit of a downer but then he is the bad guy.

I’ve never done any philosophy, but the idea of no knowledge without belief suggests that philosophers are talking about a specific definition of the word. Knowledge of a tree, or how to make soup doesn’t require belief, merely the existence of trees, or of recipes. Belief in my mind is faith in something without supporting evidence. If that evidence is provided, you no longer need to believe in it, it would simply be a fact, or item of knowledge.

I don’t see one necessarily leading to another, although I could see the lines being blurred at the moment of inspiration.

[i]The belief that belief is bad is a belief.[/i]

Yes, but it’s a linguistic problem as the two aren’t equal.

I think the problem is better reduced to this: it’s not “belief” versus “agnosticism” as much it is certainty versus doubt.

And again don’t be slave to words. The different quality between the two positions is that, as Erikson implies when talking about exploration, “doubt” is not a fixed state or destination, whereas certainty implies that questions are over and that one reached the end of the journey.

Even worse, that usually leads, as Bauchelain well explains, to the desire to deliver conformity and “enlighten” those who are of a different opinion.

Bringing the problem back to T’lan Imass, you can see where “certainty” leads: the cessation of choice.

Forgot to add a little quote:

Emancipor winced, overwhelmed by a flood of guilt. ‘Can there be no second chance, Paladin?’

‘Ah, you are a saint indeed, to voice such sentiment. The answer is no, there cannot. The very notion of fallibility was invented to absolve mortals of responsibility. We can be perfect, and you can see true perfection walking here at your side.’

‘You have achieved perfection?’

‘I have. I am. And to dispute that truth is to reveal your own imperfection.’

😉

Whatever the philosophical/linguistic underpinnings of my questions and thoughts here (and I’ll grant you, they could no doubt use some refining on my part), and whether we’re talking “belief”/”agnosticism” or “certainty”/”doubt”, I still see a duality that seems to play into the very thing that is to be avoided.

No way around this, I suspect, since to wholeheartedly embrace “doubt” (whatever that would mean) would likely make it impossible to get through the day; we are sustained (and, I would argue, to some extent *freed*) by what certainties, or imagined certainties, we detect or construct.

I think the origins of my questions on this topic have to do with the fact that such doubt or lack of certainty is quite fashionable in current fiction. Yes, there are the John Ringos etc., but there seem to be many writers (and filmmakers) for whom heroism is grotesque, embarrassing. Since I just saw “The Eagle” last night, that film can serve as a brief example (spoilers ahead).

The movie revolves around the efforts of Marcus Aquila, son of a legionary who lost the eagle standard in northern Britain, to regain the eagle and restore his family’s honor. Marcus’ slave, a native Briton, joins him on the quest.

Through the whole movie, you can see what they were trying to do: move the audience back and forth between sympathizing with one side and then the other. In the climactic scene, the leader of the Britons kills his own son in front of everyone, presumably to show how cold and evil he is, and that we should really get behind the Romans – but after the battle, there’s the requisite breastbeating about how both sides fought “for honor”; men from both sides were cremated together in what, presumably, was supposed to be a moving scene.

Unfortunately, the film was just a train wreck. The writer(s) seemed unsure what to do – and I would say their lack of vision (can I call it a lack of certainty?) played a role in their inability to present characters and a story I cared about.

In his original post, Erikson says that “a work of honest fiction is not propaganda, polemic, or didactic diatribe” – itself a statement of intense certainty, as it presupposes some intimate knowledge of the interiority of writers over centuries. The implication is that “honest” fiction (i.e., good? worthwhile? hard to escape the suggestion that that is a value statement) is open, exploratory, “doubt”ful.

But there are degrees of freedom or tyranny in art, as in politics. “Henry IV, Part 1” is an example that comes to mind when I think of open or exploratory narrative. So is “The Eagle.” When I think of a “closed”, “certain” fiction, I can think of John Ringo. But I can also point to Dante, “Beowulf,” and “Hamlet”.

Where does Erikson’s work come down in all this? I’m not equipped to answer that question, but I can say that the Malaz series seems to have come along at just the right time, when readers around the world are apparently quite willing to embrace and explore all this uncertainty, in fact to see there a kind of salvation, like Bottle and the rest worming their way under the molten wreckage of Y’Ghatan.

But the imperative for those soldiers was escape, not exploration, and escape may be an apt metaphor for the goal of those disillusioned by what they see as propaganda and polemic: escape from tyranny of vision – artistic, political, or otherwise – escape from all that weight of history, tradition, and terror. In the Y’Ghatan scene, Erikson reverses the archaeological motif that runs through his series: here, the layers upon layers of detritus and history don’t serve as our foundation, don’t lift us up to greater heights; they crush us down.

All I’m saying, or trying to say, is that, despite all the complications in the series, despite all the twists and elements of uncertainty, there is a vision here, or visions; arguments are being made, positions staked out. For the writer, approaching the proceedings with a degree of humility is certainly admirable, but in the end you still have the story on its own, out in the world, saying things.

Which is no bad thing.

This really makes me want to write a short story right now and try that hover around it edging closer as the story progresses….. Funny enough this seems to have helped me arrange my thoughts as to how to incorporate a theme in a story more than any english teacher so far..

Thank you for taking the time to write this, I have greatly enjoyed these posts!

Anciously awaiting The Crippled God,

Bob Vernen