Instead of running away from reality by writing or reading fantasy fiction, perhaps we are actually facing reality in the way that helps us understand it best?

“Many reviews are useless because, while purporting to condemn the book, they only reveal the reviewer’s dislike of the kind to which it belongs.”

– C.S. Lewis, On Science Fiction

The life of a science fiction and fantasy reader is marked with frustration whenever one ventures out into the world of criticism. The self-proclaimed literati are more than happy to outright dismiss the genre as a whole – let alone individual works – as frivolous and of no literary value.

Last week, I quoted the following from Germaine Greer, an Australian writer, academic, journalist and scholar of early modern English literature and currently the Professor Emeritus of English Literature and Comparative Studies at the University of Warwick:

“It has been my nightmare that Tolkien would turn out to be the most influential writer of the twentieth century.”

Greer added the following in winter/spring 1997 issue of W, the Waterstone’s Magazine:

Greer added the following in winter/spring 1997 issue of W, the Waterstone’s Magazine:

“The books that come in Tolkien’s train are more or less what you would expect; flight from reality is their dominating characteristic.”

As I said last week, I am returning to the underlying assumption made by Greer in this quote that “flight from reality” is any issue at all.

From a personal point of view, I have much to say on the matter that I believe is relevant.

My day job sees me working as an environmental journalist, reporting on the findings of scientists the world over as they continue to delve deeper into what is happening to our planet. Day after day I am confronted with the ever-deepening facts that humanity has put itself on a path that could very well become untenable for us as a race before too long.

On top of that, I suffer from anxiety and depression which have and continue to make serious impacts on my life over the last seven years. Much which is taken for granted by many is withheld from me. I do not complain; it is simply the way of it for the moment. But as a result of facing the deterioration of our planet’s environment, ecosystems and climate each and every work day, and my own mental inadequacies, I do not necessarily enjoy the idea of relaxing into that same world when I read (let alone watching the news).

If it wasn’t for words – the chance to read them and my ability to write them – I would be a much sorrier person.

But that is only an excuse to delve into an escape, and though an important aspect of my argument, it’s not the whole of it: for although a unicycle might be manageable for some, a bicycle with two wheels is a much more stable mode of transport.

From an academic point of view, there is much that has been written about the validity of fantasy as a means of portraying a mirror to our own world. Terry Pratchett, for example, is one author who has made something of an art form out of parodying our reality in a fantastical realm where everything is just a little … off.

But there are those for whom fantasy literature is a means to say what other forms of literature simply cannot. C.S. Lewis puts it well in his essay “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s To Be Said”:

But there are those for whom fantasy literature is a means to say what other forms of literature simply cannot. C.S. Lewis puts it well in his essay “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s To Be Said”:

“The Fantastic or Mythical is a Mode available at all ages for some readers; for others, at none. At all ages, if it is well used by the author and meets the right reader, it has the same power: to generalize while remaining concrete, to present in palpable form not concepts or even experiences but whole classes of experience, and to throw off irrelevancies.

This is the first half of his underlying theme for the essay; the idea that fantasy is not necessarily a genre everyone has to like, but when one does enjoy it, it has a better chance at presenting the authors aims then other genres. But Lewis continues;

“But at its best it can do more; it can give us experiences we have never had and thus, instead of ‘commenting on life’, can add to it.”

And this, I think, is the important part of the fantasy genre that many people are far too willing to skip over; its ability to show us whole experiences, put us into those experiences and make us live them.

Think of when you last read a biographic text of some sort. For many, if not most, the biographical genre is dull, dry, and even when written by the best, does not necessarily convey much more than the facts of the matter.

James Holland in his book Together We Stand: America, Britain and the Forging of an Alliance, opens with the story of Trooper Sam Bradshaw of the 6 Royal Tank Regiment, at the time deployed in Sidi Rezegh, Libya, in November of 1941. The story that Holland tells is undeniably horrific and terrifying for Sam Bradshaw, but I’ve no idea what it would have felt like to be in a Nuffield A15 Crusader tank, nor what it smelt like when his wound started to become gangrenous, nor the horror at finding out he was to be sent back to the front, instead of home to England and the woman he loved.

Tom Shippey brings to light in the foreword to his book J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, several prominent 20th century authors, who regularly enter into the lists of favourite authors of the populous and literati alike, that he describes as ‘traumatized authors’ as a result of what they had seen and been through prior to their prominence as authors. Authors such as George Orwell and C.S. Lewis were both shot on the battlefield, while Kurt Vonnegut was a survivor of the firebombing of Dresden (not to mention Ursula Le Guin, the daughter of Theodora Kroeber, who, according to Shippey, “wrote three different accounts of ‘Ishi’, the last survivor of the eventual total elimination of the Yahi Indians of California”).

Personal injury, unparalleled city-wide destruction, and genocide: these are not topics which are easily understood when only the facts are provided.

Shippey writes that Kurt Vonnegut “spent twenty years wondering how he could write about the central event of his life, the destruction of Dresden, in a way that could possibly be appreciated, while dealing with people who preferred to deny or ignore it.”

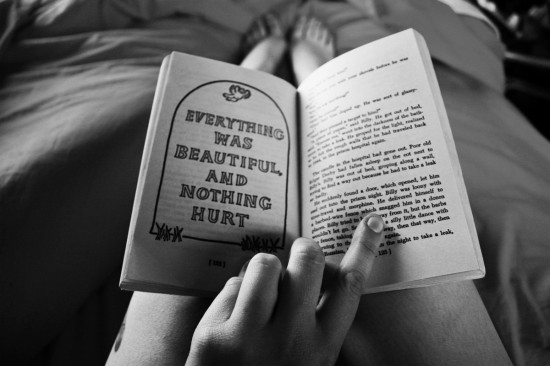

(For those wondering, Vonnegut depicted the “utter destruction” and “carnage unfathomable” of the Dresden firebombing in his science fiction novel Slaughterhouse-Five, which takes a soldier named Billy Pilgrim into a prisoner of war camp in Dresden to witness the destruction, all the while sending Billy through time, whether it be in his mind or in the books reality.)

Tolkien, as another quick example, saw his two best friends killed during World War I: is it any wonder there was such a heavy influence on good versus evil in his writings?

Tolkien, as another quick example, saw his two best friends killed during World War I: is it any wonder there was such a heavy influence on good versus evil in his writings?

It seems, from the small sample that I’ve provided which itself is culled from a larger sample, that those who experienced horrific evil could find no other outlet to write, than fantasy. It allowed them to express the horror that they had suffered, or seen, in a way that not only provided the facts of the event, but the emotions as well.

And what is a story if not something to play upon the emotions of the reader? The answer is a non-fiction book which just gives you the facts of the story.

What fantasy gives the author, what it allows him to accomplish, is something that cannot be done in any other form literature. Even autobiographical accounts and those stories that do not depart from reality lack the ability to fully put the reader into the shoes of someone experiencing trauma. Something of the way in which it separates the reader from the world around them, helps them to better understand the situation of the characters they are interacting with.

So when Germaine Greer sneeringly notes that Tolkien’s “dominating characteristic” is “flight from reality,” one really has to wonder whether Greer has any understanding whatsoever of what Tolkien had written. Tolkien had not fled reality; rather he had turned to face it, understood it in a way that very few of us will ever be able to and poured it into his work.

Photo Credits

“The Lord of the Rings” wallpaper www. scifiworld.net

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, 2003, (c) New Line/courtesy Everett Collection

“Today I finished Slaughterhouse-Five” ambird @ Flickr.com. Creative Commons. Some Rights Reserved.

I don’t get why fantasy is looked down so much. In my view the genre of fantasy gives the author total and complete control over their story. This amount of freedom is not available to any other literary genre. Although we would like to think that there is something important to be found in our favorite books the truth is that books are a form of entertainment no different than any other and no other genre in no other media allows the complete and total immersion that fantasy books do.