“It is unlikely that there will ever be an author who has captured my imagination as much as J.R.R. Tolkien,” says Joshua S. Hill, who explains why the works of Tolkien engage him like no other author.

Over the past three weeks I have looked in depth at the world of fantasy fiction, and the negative light in which it is often viewed. For any who have read those previous articles, the fact that I am an avid J.R.R. Tolkien fan will probably not come as much of a surprise.

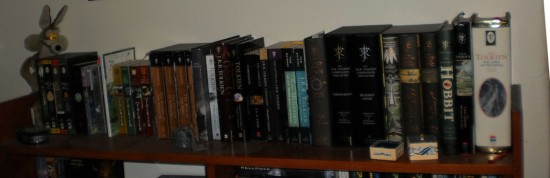

That is my collection of books by, or on, Tolkien. It makes me happy to see that shelf filled, a rare sight these days considering that the books are normally spread throughout my lounge room and office as I work on a book based on the work of Tolkien.

So this week, I wanted to take a moment and explain my love affair with the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

I imagine that my story began, like many others of my generation, with a viewing of The Fellowship of the Ring. I had already asked my dad for a boxed set of The Lord of the Rings + The Hobbit for Christmas (it’s the green boxed set at the left end of the photo) as the trailers for the movie had me thoroughly excited.

I love recalling the fact that, as I walked out of the first of five screenings of The Fellowship of the Ring, I turned to my father and said “They’re going to be making a lot of money out of me.”

I was right. Again.

I currently own three copies of the Fellowship, and two each of the remaining two movies in the trilogy (I still need to get my hands on the third editions of each of those); not to mention the horde of books you can see in that image up there and a few other odds and ends.

Another aspect of that first screening of Fellowship was my confusion at the end of the movie: Sam and Frodo are looking out over the Emyn Muil and onto the Dead Marshes and beyond, and then the movie closes, and I’m all of a sudden confused. I had thought that the ring would be destroyed in the first movie and that other adventures would follow in the subsequent movies.

Much was made clear when I finished reading the books (all three in the space of seven days), including an explanation of the added confusion my father had introduced when he referred to the “Horse people of Rohan.” Needless to say, I was glad when there were no centaurs wandering around Rohan when I got to The Two Towers.

Much was made clear when I finished reading the books (all three in the space of seven days), including an explanation of the added confusion my father had introduced when he referred to the “Horse people of Rohan.” Needless to say, I was glad when there were no centaurs wandering around Rohan when I got to The Two Towers.

Completion of the trilogy left me with a deep desire to read more. Much more. I soon made my way to a local bookstore and asked for “more books like The Lord of the Rings” and walked away with The Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks (some might say that’s not a brilliant start, but I enjoyed it).

My introduction to the world of fantasy is completely laid at the feet of Tolkien, and no one since Tolkien – with the possible exception of Steven Erikson [Ed. Steven Erikson also writes for Life As A Human] has managed to create a universe so complete and compelling.

Tolkien’s magical world is truly an achievement very few will ever reach in the decades to come, and that might be because of the incentive of those trying.

You see, Tolkien didn’t write The Lord of the Rings to make himself a best-selling author. He did it for two reasons, as far as I can tell: first, to fulfil the requests of those who had read The Hobbit and wanted more; and second, to tell the story of the languages that he had created.

Tolkien spent much of WWI working on what would later become the works of The Silmarillion. But even those stories were simply a backdrop for his Elvish languages. He had started work on these in 1910, when he was 18 or 19, and went on to create at least 15 Elvish languages, and some half-dozen or more (the exact count is unknown as many of his linguistic papers are still unpublished).

Tolkien spent much of WWI working on what would later become the works of The Silmarillion. But even those stories were simply a backdrop for his Elvish languages. He had started work on these in 1910, when he was 18 or 19, and went on to create at least 15 Elvish languages, and some half-dozen or more (the exact count is unknown as many of his linguistic papers are still unpublished).

Names and language created the stories for Tolkien, not the other way around. One need only read one of the many biographies (though I would recommend you go no further than reading those written by Humphrey Carpenter and Thomas Shippey) to have Tolkien recount for you himself through the many letters he wrote that he had no idea of where he was going when he started writing The Lord of the Rings, nor, as we find out as we read through The Histories of Middle Earth, well into the process either. It is not until well after leaving Rivendell that Tolkien finally begins to see the germ of his creation, and the Ring and the wraiths and the doom of what he is writing begins to reveal itself.

That is a very heartening thing to know, as a writer myself. I like the idea of writing my way into a story, rather than plotting it out to the nth degree. I like the surprise and discovery, because not only am I being entertained, but if I’m entertained, it stands to reason than so too will the reader be entertained.

Tolkien’s work goes well beyond that of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit however, and I do not strictly mean his Legendarium or The Silmarillion either.

One need only look at the Wikipedia page for Beowulf, and you will find eight references to Tolkien. In fact, Tolkien is still regarded as one of the foremost scholars of Beowulf research, not to mention being one of the foremost experts of the 20th century in Anglo-Saxon and Middle English.

To quote from Wikipedia:

Lewis E. Nicholson said that the article Tolkien wrote about Beowulf is “widely recognized as a turning point in Beowulfian criticism”, noting that Tolkien established the primacy of the poetic nature of the work as opposed to its purely linguistic elements.

— Bill Ramey, “The Unity of Beowulf: Tolkien and the Critics”….

Tolkien is also responsible for one of the definitive translations of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Sir Orfeo and Pearl, Middle-English poems that are at the basis of learning about the literature of that period.

For me, J.R.R. Tolkien is a role model who I hope to follow closely. I want to write both fictionally and academically, and though I may not reach his level of intelligence and renown, I can definitely try.

Photo Credit

“J.R.R. Tolkien” BBC

Please Share Your Thoughts - Leave A Comment!