Much is being written these days about the Catholic Church, and especially about the hierarchy of the Church. The failure of bishops everywhere to stop the sexual abuse of children by priests has left Catholics and non-Catholics alike wondering how these men could have so callously turned their backs on the terrible reality of the suffering of children. This failure of pastoral care for the most vulnerable of their flock has cast a shadow over the order of Melchizedek, from the lowliest parish priest to the Holy Father himself. It has cast a shadow over the entire Church.

Many are now wondering what the clerical culture of the modern Church has to do with the life and the mission of Jesus of Nazareth. Yet there are priests in small pockets of society whose ministry is so full of love, so steadfastly directed toward the most marginalized—as was the ministry of Jesus himself—that the light of their service dispels some of that shadow. One of these priests is Jesuit Father Gregory Boyle, founder of Homeboy Industries of Los Angeles.

In 1986, at his own request, Father Greg was appointed pastor of Dolores Mission in the Boyle Heights neighbourhood of Los Angeles, the poorest parish in the archdiocese. The church is located between the public housing projects of Pico Gardens and Aliso Village, home at that time to eight active street gangs. Under the direction of Father Greg and parish members, Dolores Mission became a kind of community centre where gang members could gather to just “kick it.”

In 1988, when it became clear that what gang members wanted most was a job and that businesses were not particularly interested in hiring a guy covered in gang tattoos, the parish launched Homeboy Industries. Over twenty years later the organization is offering tattoo removal services, psychological and employment counselling, and job placement in the community or in one of several Homeboy industries, including a bakery, a silk-screening factory, and the Homegirls Café. 12,000 gang members go through the doors of Homeboy Industries every year, and the lives of many of them get turned around with the help of Father Greg and his staff.

But Father G (or simply “G”), as he is called by his homies, is much more than a social worker.

“Once I was in my office and there was this gang member named Louis, seventeen years old and happier than a clam, big huge smile on his face, and he says, ‘Here I am! I just got out yesterday, and you were the very first person I came to see’. And never in my life had I seen more hickies on a human being than on this guy Louis—all over his neck, on his cheeks; it was just unbelievable. And I said, ‘Louis, I have a feeling I was your second stop’. Well, we howled with laughter, and suddenly there’s kinship so quickly.”

Father Greg uses his steamer trunk full of stories—touching, humorous, inspiring, and sometimes heartbreakingly tragic—about gang members to make his point about how we relate to “the other” in this world. His stories reflect his familiarity with the gang culture, with the language gang members use, with the horrors and the hopelessness of their childhoods; most important, however, they reflect the humble, deeply intimate kinship he has established with these men and women.

Father G’s point in the Louis story: “It’s not about service provider or about service recipient; it’s about us belonging to each other.” Because most of the young men who join gangs have had no one to belong to in their lives, Father G calls each of them mijo (“my son”), and he loves and cares for them like sons.

CNNs Anderson Cooper, an admirer of Father Greg and of his work, once asked the priest if he wasn’t afraid of being taken advantage of. Father G’s reply was that he gives his advantage away.

The love Father Greg feels for his homies is in fact returned in equal measure. When they learn he has leukemia, there is an outpouring of support and concern expressed in unique ways that are both poignant and funny. One such expression is especially touching. When Father G gives a public talk to raise awareness and money for Homeboy Industries, he usually takes a couple of homies with him to speak to the audience of their experience. At the end of the Mass that follows one of these events, on this occasion held at a university, the university chaplain invites the members of the congregation to come forward and lay hands on the priest for the healing of his leukemia. Father Greg is embarrassed by this gesture, until it is the turn of Matteo, one of the homies, to lay on hands:

My head is inclined and eyes closed. He has my head in a vise grip, and he’s trembling and squeezing it with all his might. He leans right into my ear as he does this and can barely speak through his crying.

“All I know,” he whispers, enunciating with special care, “is that…I love you…so…fucking…much.”

Now I am crying.

(The next day he says “’Spensa for that blessing I gave you. I don’t know how to do ‘em.” I assure him it was the best of the bunch.)

Father Greg’s talks are like homilies. But his words do not come from moral theology class or from scripture studies; they come from the gritty everyday reality of his ministry, which is his life. He knows the language of the gangs and he uses it. In one of his stories, he tells of being in church and saying a “long-ass prayer” while blessing a former gang member’s 18-year-old daughter who is going away to college. When she tells him she is going to study forensic psychology, Father G, appropriately impressed, says in his best gang voice, “Daaaamn….forensic psychology?”

Greg Boyle does not for a moment think that he is Jesus. But there is no question that his ministry models that of Jesus: “We stand there with those whose dignity has been denied. We locate ourselves with the poor and the powerless and the voiceless. At the edges, we join the easily despised and the readily left out. We stand with the demonized so that the demonizing will stop. We situate ourselves right next to the disposable so that the day will come when we stop throwing people away.”

The work of Homeboy Industries and of Father Greg Boyle has been recognized worldwide. In his talks and in his recent book, Father G mentions—usually with a slightly sardonic tone—that the facilities of Homeboy Industries have been visited by such luminaries as the mayor of Los Angeles, U.S. First Lady Laura Bush and Vice-President Al Gore as well as the official representatives of Prince Charles of Great Britain.

Notably absent from the list is the Archbishop of Los Angeles.

Due to significant reduction in private and corporate donations resulting from the recession as well as to reductions in public funding, Homeboy Industries was forced in the spring of 2010 to lay off most of its employees. Core businesses and services remain open, however.

Father Greg has been cancer-free for several years. His book is Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion.

Photo Credits

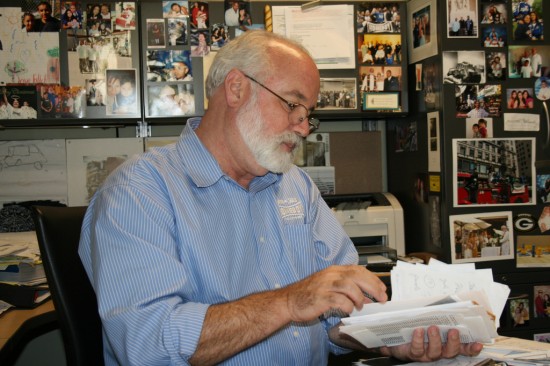

“Father Greg Boyle” Father Greg as he’s known to all, started Homeboy in 1988 determined to do something to address LA’s notorious gang violence. It’s the biggest and most successful anti-gang programme in the US but is badly short of funds. The economic downturn means corporations and foundations can’t afford to be as generous as in the past. bbcworldservice @ Flickr.com. Creative Commons. Some Rights Reserved.

“From Gangs to Cakes” One of the workers at Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles. The project sees about 12,000 young men and women through its doors every year. Many are former gang members , others are ex drug dealers. Homeboy Industries employs them in its bakery and cafe or tries to find them work elsewhere. bbcworldservice @ Flickr.com. Creative Commons. Some Rights Reserved.

Recent Ross Lonergan Articles:

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Four

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Three

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Two

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part One

- Bullying, Fear, And The Full Moon (Part Four)

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Kevin Aschenbrenner, Life As A Human. Life As A Human said: New Article, The Jesuit and the Homies: It’s All about Kinship – http://tinyurl.com/2dvvnyd […]