There’s nothing worse than an unc ooperative cobra. Even if it is 50 years old, there’s no need for it to make an asp of itself.

ooperative cobra. Even if it is 50 years old, there’s no need for it to make an asp of itself.

Travelling in India with a Rajput interpreter has advantages, not the least of which is being able to ask the locals questions.

But often, it was the little things that Yaduvendra Singh (Yadu) picked up as an aside which really enhanced the experience.

Take the Indian snake charmer, for example. The well-dressed, turbanned gipsy sitting in the dust in a formal jacket put on a dignified pose when faced with the camera, but his long-time mate, the snake, didn’t want to play the game.

For a while there, the cobra refused to face the lens and when the snake charmer tried to coax it, it struck out at him. What the gipsy quietly hissed in Hindi was priceless: “Come on. Don’t embarrass me ….!”

In the broad expanse of India’s 3.28 million sq kms, the town of Nimaj is less than a speck. But it’s here that you can meet some of the descendants of the forefathers of Europe’s gipsy (also known as gypsy), or Roma, people.

In the broad expanse of India’s 3.28 million sq kms, the town of Nimaj is less than a speck. But it’s here that you can meet some of the descendants of the forefathers of Europe’s gipsy (also known as gypsy), or Roma, people.

The snake charmer, or Sapera, as he is known, was one of a number of gipsies the Indian Government has resettled around Nimaj.

His roving days may be over, but that didn’t stop the Sapera from putting on a bit of a show. He also expected a few rupees for his trouble, of course.

With a population of aro und 7,000 people – a drop in the ocean of this sprawling country’s teeming 1.28 billion inhabitants – Nimaj doesn’t rate a mention in Lonely Planet’s hefty guide to India.

und 7,000 people – a drop in the ocean of this sprawling country’s teeming 1.28 billion inhabitants – Nimaj doesn’t rate a mention in Lonely Planet’s hefty guide to India.

It’s easily overlooked even in Rajasthan, a northern Indian state with a population of more than 56 million people.

But it still has “royal rulers”, the Thakur sahib of Nimaj, Bhagwati Singh, and his wife, Divya. Along with his brother, Bharrat Singh, they operate Nimaj Palace as a hotel, the origins of which date back to 1548.

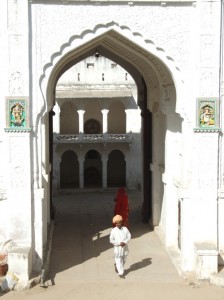

The palace’s rendered ramparts are an imposing structure within the tightly-packed town and the twin gods – Ganesha, the elephant god of good fortune and demon-slayer Dhurga, the goddess of cosmic power — still look down upon those who pass through the 10m-high portal gates into the chowk (courtyard), just as they have done for more than 450 years.

A three-hour drive south-west of Pushkar, in the Marwar provi nce of Rajasthan, Nimaj is set amidst wheat and millet fields, the mud-plastered houses of it’s surrounding farms and villages linked by dusty roads and narrow pathways, the tilled fields separated by hedges of thorn trees.

A three-hour drive south-west of Pushkar, in the Marwar provi nce of Rajasthan, Nimaj is set amidst wheat and millet fields, the mud-plastered houses of it’s surrounding farms and villages linked by dusty roads and narrow pathways, the tilled fields separated by hedges of thorn trees.

On the official government road map, unlisted Nimaj should lie equidistant between Jaitaran, Raipur and Beawar. But it doesn’t. Apparently it didn’t warrant the ink.

But it does exist. It is there. And it’s laughing, joking children, and welcoming inhabitants leave warm impressions on fortunate travellers.

At a local school, students in spotless uniforms ask serious questions about Australia, and especially cricket. “Ricky Ponting” is their catchcry. They say they want India to have no part in nuclear proliferation.

Tourism is a relatively new industry in Nimaj, emerging over the past ten years as a way for villagers to supplement their small rural income.

Farmers supply the Nimaj Palace with fresh vegetables and meat, hotel staff are the sons and daughters of local villagers, and their leather shoes are made by the town cobbler, their uniforms by the local tailor.

Fresh milk and lamb comes from the market and down a narrow street, past the carpet seller, silversmith and ironsmith, the sound of a diesel engine can be heard plugging away as the miller grinds millet and wheat to make flour for baking.

In a narrow recess beneath the arched entrance to the walled old town, the barber charges 24 cents (10rp) for a shave and is outwardly happy to have a tourist or two in his chair on which to practice his carefully spoken, polite English.

And in the surrounding villages, where Gujjar cattle and sheep herders and their families live and where the roving gipsies have been forced to put down roots, the locals are happy to meet and greet visitors outside their very, very humble homes.

DNA evidence shows India was the birthplace of the world’s gipsies.

The bloodline of the Roma people, or gipsies, dates back to pre-1000AD, when their forefathers migrated westwards from northern India, spreading throughout Europe.

Today in Rajasthan, the Roma have evolved into a variety of castes, including puppeteers (Bhat), snake charmers (Sapera) and jugglers (Kamad), along with the musician castes of Bhopa, Langa and Manganiyar.

We visited the walled yard of a potter, the only one in his village.

a potter, the only one in his village.

Sohan Lal has been a potter for 30 years. Like his father, his grandfather, and as far back as he can remember, all the men in his family have been potters.

Rolling and kneading the clay, he mixes it with sawdust to help it retain moisture.

Then he spins a stone wheel balanced on a wooden stake embedded in the ground, speeding it up with experienced thrusts of a short, heavy stick.

When the wheel is up to speed, he throws the clay in the middle, and within minutes, his clay-stained, long-fingered hands have fashioned yet another pot, like the tens of thousands created before him by his forefathers, down through the ages.

As the potter demonstrated his craft, in the background his young son accidentally knocked a pot off the table and it smashed on the ground.

The potter was overheard muttering in Hindi in exasperated tones: “Oh no, here we go…”

An itinerant barber stopped to talk to Yadu in the village square.

The interpreter inquired after the health of the old man, or baba, and where he was heading.

The corners of his watery eyes sq uinted and beneath his grey, curling moustache, his deeply etched face creased into a gentle smile. He told how his family could or would not support him, so he walks from village to village, house to house, with his small, battered leather case containing his scissors, a razor and metal spatulas, offering to shave men, cut their nails or clean their ears, for a few rupee.

uinted and beneath his grey, curling moustache, his deeply etched face creased into a gentle smile. He told how his family could or would not support him, so he walks from village to village, house to house, with his small, battered leather case containing his scissors, a razor and metal spatulas, offering to shave men, cut their nails or clean their ears, for a few rupee.

Sleeping and washing wherever he could, the baba’s destiny was to endlessly roam to earn enough to eat, until he physically could no longer do so.

While the Nimaj Palace hotel offers regular village, school and rural tours, and villagers operate bullock and camel cart rides for tourists, agriculture is still the main source of income in the region.

“Now the farmers sell their fresh vegetables to us to prepare for the guest’s meals,” says the Thakur sahib.

Nimaj Palace is the only hotel in town, and there’s generally always somebody in a turban wanting to do something for you.

There is no intention of completely restoring the palace. Part of its ambience lies in its rabbit-warren architecture and its ramshackle, rustic charm.

Guests awaken to the sound of a flute being played in the courtyard and the cooing and flapping of pigeons outside the wooden shuttered windows.

Not far from the town, in a narrow laneway amongst mud-daubed houses near a Gujjar shepherd’s home, a young girl is heard but not seen, singing sweetly in Hindi.

Not far from the town, in a narrow laneway amongst mud-daubed houses near a Gujjar shepherd’s home, a young girl is heard but not seen, singing sweetly in Hindi.

It’s near dusk and the shepherd is outside his house with his wife and two young children, waiting to be introduced to the tourist visitors by Yadu, the guide.

Shyly, he shows us pictures of Bollywood stars pinned to the rain-stained walls of his front room.

He, like most Gujjar, is Hindu and a vegetarian. The shepherd owns 56 sheep, raising them for their milk, wool, meat and manure.

A sheep produces about 200ml of milk a day, and a litre will earn him 24 cents (10rp) at the market.

The shepherd sells the wool for 73 cents (30rp) a kilogram.

But a tractor trailer of sheep dung sells for about $73 (3000rp).

So, if a Rajasthani shepherd says he is making a crap living, he’s actually doing quite well.

* For further information on Nimaj and the Nimaj Palace Hotel, visit www.nimajpalace.com.

Photo Credits

All photos © Vincent Ross

“Nimaj – India – Snake charmer”

“Nimaj – India – lake sunset”

“Nimaj – India – Snake charmers”

“Nimaj – India – Village cow”

“India – Village potter working clay”

“Nimaj – India – Village life”

“Nimaj – India – Water woman”

Thank you for sharing this story of your journey to India. I had no idea that gypsies originally came from India. I will be sure to tell my husband who has some gypsy ancestors in the very distant past.

I have visited southern India three times myself – 1997, 1999 and 2007. I was surprised at how much India had grown in industry, especially Bangalore and the computer industry since 1999. I love the Indian people that I met on each trip. They were so friendly.