In the aftermath of witnessing a young man’s death, the writer does what he knows — he writes.

5. Writing the Story

Back at the Hotel Rembrandt, Alison opened a bottle of plummy, five-year-old Crianza wine and arranged some bread and sheep’s cheese on a plate while I tested the iron railing surrounding our balcony with a kick. Our room on an upper floor was spare, run down, sweltering and cramped, even for two people. The balcony was cramped too. Regardless, it made our room tolerable in crowded, hot Barcelona. From there I watched people emerge in the relative cool of the evening onto the balconies of the buildings across the street. I couldn’t eat. The cheese just tasted dry. All I remember of the wine is how it numbed. Drinking or eating anything made me feel guilty. I should be grieving, not indulging in the pleasures of the senses.

Back at the Hotel Rembrandt, Alison opened a bottle of plummy, five-year-old Crianza wine and arranged some bread and sheep’s cheese on a plate while I tested the iron railing surrounding our balcony with a kick. Our room on an upper floor was spare, run down, sweltering and cramped, even for two people. The balcony was cramped too. Regardless, it made our room tolerable in crowded, hot Barcelona. From there I watched people emerge in the relative cool of the evening onto the balconies of the buildings across the street. I couldn’t eat. The cheese just tasted dry. All I remember of the wine is how it numbed. Drinking or eating anything made me feel guilty. I should be grieving, not indulging in the pleasures of the senses.

The wine loosened our tongues and for the first time since the accident, we each told the other everything we’d been thinking. It came flooding out.

“I’m glad we didn’t bring the kids here,” Alison said. She cried, empathizing with the young man’s parents. Over the years, we’d talked about this trip and debated whether or not to bring our own kids. We wanted to travel with the kids as much as possible, educate them about other cultures and other places, but in the end decided to stick with our original plans.

A terrible thought struck me. “What if they’d been with us?”

We relived the accident over and ove r, reviewing the details, each from our own point of view, Alison up on the bridge, not daring to look over, waiting for me to come back. “I didn’t even see you go.” The four singing girls who ran back to the bridge after the young man fell. One looked over. We saw them later on the number 24 bus. “She didn’t look well,” Alison recalled.

r, reviewing the details, each from our own point of view, Alison up on the bridge, not daring to look over, waiting for me to come back. “I didn’t even see you go.” The four singing girls who ran back to the bridge after the young man fell. One looked over. We saw them later on the number 24 bus. “She didn’t look well,” Alison recalled.

I remembered leaving Parc Güell. When I looked back to the police cars and the crowd that had gathered, I spotted two young men, one hunched, vomiting onto the ground, the other with his hand on the back of the first.

It was almost midnight by the time we got ourselves out of the room to look for late tapas. The city was closing down, but we found a bar on the square before Barcelona Cathedral. We ordered beer and watched people where, that afternoon, we’d enjoyed a trio who’d hauled an upright piano into the square to play Dixieland jazz.

A fire truck and ambulances screamed past on a nearby street. I looked at Alison, wide-eyed. “You need to stop because you’re not the only one suffering tonight,” she scolded. She was right to call me on such self-indulgence. We had a weight to carry, it was true, but nothing like that of the man’s companions or parents. This was only an accident; I hadn’t witnessed a murder. We hadn’t found ourselves in a terrorist attack or even a bad traffic accident. I hadn’t survived genocide or a plane crash. It takes nothing from the victim to admit to self-indulgent grief.

After the tapas bar closed, we followed the sound of music to a makeshift stage in the middle of a street where a band complete with four-piece horn section played, awash in red light. We stood there invisible, double the age of everyone else, the faces a reminder that Barcelona is a young person’s city. Clothing of all kinds is minimal for the young women and men walking, shopping and touring, all trying to look as beautiful as possible – so much bare skin, sandals on every foot, short dresses of thin fabrics. In Barcelona that night, any cynicism and jealousy I harboured against the young waned. Toward my fellow travellers I felt nothing but warmth and hope.

Back at our hotel, I co uldn’t sleep. I sat on the balcony on our last night in Barcelona, watching the night people. A church bell rang three times and I thought of him. Where is he at 3 a.m.? In a hospital ICU? A morgue? Where is he from? Alison said she thought she’d heard him speaking Spanish. I decided to write down everything I could of the accident. I’d need it later.

uldn’t sleep. I sat on the balcony on our last night in Barcelona, watching the night people. A church bell rang three times and I thought of him. Where is he at 3 a.m.? In a hospital ICU? A morgue? Where is he from? Alison said she thought she’d heard him speaking Spanish. I decided to write down everything I could of the accident. I’d need it later.

Alison awoke to find me with my notebook. “This is what I can give him,” I told her. As soon as the words were out of my mouth, I realised this too was self-indulgent opportunism. Who was I fooling? Why was this my motivation, to give something to a dead man by writing about him? What kind of gift matters to the dead anyway? To be remembered? To grant the illusion of meaning, of story, of plot to a set of random events otherwise known as a life? I could have removed my shirt and rested his head upon it. Wouldn’t that have been the better gift?

And yet, that’s all I had, so I wrote…

On a recent trip to Barcelona, I witnessed a man in the glory of his youth fall from a work of art.

In contrast to the organic eruption of the Nativity Façade, the bleak Passion Façade opposite appears constructed of bone. The Sagrada Familia is a work of art that gracefully balances the tension between life and death.

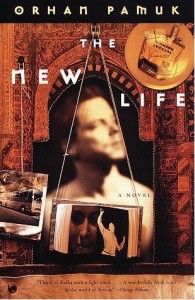

I read a book one day and my whole life was changed.

Writing about the accident changed my mind about Orham Pamuk and The New Life, which I finished reading within a month of returning home. Risk, accident and death give us life unhindered by language and metaphor, strip it bare so we see it, feel it for what it is, a flash, a brief light between two darknesses, a treasure, something precious beyond anything else we can name.

Writing about the accident changed my mind about Orham Pamuk and The New Life, which I finished reading within a month of returning home. Risk, accident and death give us life unhindered by language and metaphor, strip it bare so we see it, feel it for what it is, a flash, a brief light between two darknesses, a treasure, something precious beyond anything else we can name.

In the days following, we would peer over the cliff edges of Montserrat – inspiration for Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia, as with the cathedral itself looking like some giant hand had dribbled wet sand into mountainous piles – lurch across the tops of the Pyrenees, cause a fender bender in Tortosa. Events like these pushed the end of life into view, lending that brief, lighted moment an intensity, a timelessness that will stay with me until there is no more.

The next day on our way out of the city, we met a German couple, Heike and Jo, in the queue for our rental car. On a weekend excursion to visit Barcelona, they’d planned to travel up the Costa Brava to watch their son compete in a sailing race.

The next day on our way out of the city, we met a German couple, Heike and Jo, in the queue for our rental car. On a weekend excursion to visit Barcelona, they’d planned to travel up the Costa Brava to watch their son compete in a sailing race.

As it turned out, neither they nor anyone else without a reservation could find a rental anywhere in the city. They were stuck, so we offered them a ride. We had only a rough idea where we wanted to go anyway. They thought of it the other way around, but Heike and Jo saved us. I found myself craving to know everything about them. They obliged and showed equal curiosity in return.

Such good company, these complete strangers, such a precious human exchange that I found my mind consumed entirely by them and by driving the unfamiliar Spanish roads. When we reached a little fishing town turned tourist attraction called L’Escala, Alison and I found a hotel while Heike and Jo called their son. As it turned out, he didn’t have time to see them, so we enjoyed a meal together. Later, they booked a room at the same hotel. By the time we parted ways, the German couple and the quiet fishing resort had removed me so far from Barcelona and Gaudi, the accident lost its shape. The video clips stopped looping through my head. We stayed for three days.

Two weeks in Spain shortened my life by that measure, but it granted me the illusion of meaning. Our trip was a random set of events that the writer in me later shaped into this story. The story might mean many things. It might mean nothing at all. It might mean that, as with writing and with reading, we travel to create contrast, to change the course of what we believe is the story of our lives. Places strike us as beautiful because they are not home. People seem interesting because they are not us. Travelling is appealing because it is not waiting. Life appears precious and fleeting because it is not the eternity of death.

Two weeks in Spain shortened my life by that measure, but it granted me the illusion of meaning. Our trip was a random set of events that the writer in me later shaped into this story. The story might mean many things. It might mean nothing at all. It might mean that, as with writing and with reading, we travel to create contrast, to change the course of what we believe is the story of our lives. Places strike us as beautiful because they are not home. People seem interesting because they are not us. Travelling is appealing because it is not waiting. Life appears precious and fleeting because it is not the eternity of death.

At the airport, Alison wanted to buy me a souvenir Barcelona t-shirt, every one of them printed with Gaudi-inspired designs. I couldn’t bring myself to accept. Wearing it would mean wearing a memory I didn’t want to be part of my story. About a month after we returned home, Alison broke it to me that she’d found news coverage on the internet of the Parc Güell incident. The young man had died.

Continued from:

The Fallen Traveller, Part I – Gaudi and the Fall

The Fallen Traveller, Part 2: Honeymoon and the Cathedral

The Fallen Traveller, Part 3: Following the Fall

The Fallen Traveller, Part 4: The New Life

References

Orham Pamuk, The New Life. (Translated by Guneli Gun). Vintage International, New York, 1998.

Photo Credits

“Dixieland Band in front of Barcelona Cathedral” © Darcy Rhyno. All Rights Reserved.

“Entrance to Paradore Tortosa” © Darcy Rhyno. All Rights Reserved.

“Montserrat” © Darcy Rhyno. All Rights Reserved.

“Watching the storm at Paradore Cordona” “Montserrat” © Darcy Rhyno. All Rights Reserved.

“Costa Brava hidden beach” © Darcy Rhyno. All Rights Reserved.

Darcy, I would have commented before this but I didn’t want to stop reading, so anxiously went from post to post, consuming each story. This is a haunting story that’s beautifully written. It’s also a legacy to the person who died in the fall. You’ve given me pause for thought. I’m tempted to get a copy of Pamuk’s book but intuitively I think I have more to learn from reading this story than his novel. Thanks for making me think. (ps you should enter this piece for an award. Hope you do.)