I love to sing. Last Saturday I had one of the most enjoyable days I’ve had in ages getting together with a group of perhaps 40 people from the Willamette Valley (plus a few from Seattle) to sing shape note songs from a hymnal first published in 1844. They met at Geercrest farm, a beautiful living history farm and education center outside of Salem, Oregon, for 2 ½ hours of singing school, a groaning board of potluck “dinner on the grounds,” and three hours of open singing.

I love to sing. Last Saturday I had one of the most enjoyable days I’ve had in ages getting together with a group of perhaps 40 people from the Willamette Valley (plus a few from Seattle) to sing shape note songs from a hymnal first published in 1844. They met at Geercrest farm, a beautiful living history farm and education center outside of Salem, Oregon, for 2 ½ hours of singing school, a groaning board of potluck “dinner on the grounds,” and three hours of open singing.

This style is known as shape note singing because the notes are printed in four different shapes – triangle (fa), circle (sol), square (la) and diamond (mi). Usually a group will sing the melody using the shape names before launching into the hymn itself. This fixes the melodic line in memory, allowing a person to concentrate on lyrics, and helps a person not trained to read music to determine relative pitch.

If anyone had told me, a decade ago, that I would find such satisfaction and pleasure from singing old hymns liberally laced with gloom and doom and Hellfire, I would probably have been incredulous. I am, after all, an educated and relatively liberal person, and while I believe in a God of my understanding and attend a generic Protestant church, lyrics of the general purport “I’m so glad I’m about to die, because I’m saved so I get to go to Heaven and be with Jesus” don’t really resonate with me.

I was also rather reluctant to sing in public with other people, because I have no formal musical training and only average musical ability. In the days before recorded music became ubiquitous, the music people made themselves sufficed for ordinary social occasions, and there was more encouragement and opportunity for mediocre musicians to develop their skills. At present, the consumer of music can have the New York Philharmonic at his command twenty-four hours a day, in quite a good reproduction, at very low cost. Why should he engage the services of singers and musicians at all, even if they are free? Why should a person bother to learn a musical instrument or train his voice, when there are few outlets for the product, and the local performer is being judged against an impossible national standard?

I was also rather reluctant to sing in public with other people, because I have no formal musical training and only average musical ability. In the days before recorded music became ubiquitous, the music people made themselves sufficed for ordinary social occasions, and there was more encouragement and opportunity for mediocre musicians to develop their skills. At present, the consumer of music can have the New York Philharmonic at his command twenty-four hours a day, in quite a good reproduction, at very low cost. Why should he engage the services of singers and musicians at all, even if they are free? Why should a person bother to learn a musical instrument or train his voice, when there are few outlets for the product, and the local performer is being judged against an impossible national standard?

I found shape note singing accidentally, when our local group, the Eugene Sacred Harp Singers, performed a Christmas concert in a church where a 12-step group I attend was also meeting. I opted for the concert. Halfway through the program, the performers handed out sheet music and invited audience members to join in. I was already a member of a church choir, and knew I was capable of choral singing, so I took the bait.

I liked the church choir, but this was different. There is no conductor – anyone can call a song, and then get up and lead it. Usually the group sings for the sheer joy of singing together, without an audience or a performance in mind. The music was written so that untrained, unaccompanied singers could unite in four-part harmony. Generally each of the four parts has its own distinct melodic line, which makes learning parts other than the melody easier. Such polyphonic music was already old-fashioned when these hymns were harmonized in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It gives shape note singing a Renaissance-era quality that is appealing to listen to.

I find that there is something intensely spiritual about the mere act of harmonizing with other people, tuning pitches so that the entire group reverberates as a whole. Harmonizing as a group, coordinating pitch and rhythm with or without articulate lyrics, is a central activity in many primitive and folk cultures. Analogous “rituals” are also found among social animals, birds, and even invertebrates. It seems probable to me that the role of musical harmony in reinforcing community cohesiveness is hard-wired and instinctive, and that I tap into it when I sing with others.

Singing shape note hymns with my tribe, with each individual equally responsible for contributing to the whole, brings me back to basics. Singing more complex music in a formal choir, with a university-trained director, attempting pieces that will only sound good if everyone relinquishes his autonomy to the director and at least some of the singers have a lot of formal training, dilutes the community-building aspect. Simply listening to a live performance creates further distance between consumer aesthetics and gut-level participation. When one is listening alone to a recording, little if anything of the community dimension of music remains.

Image Credits

Image #1 “Shape note singers, Geercrest Farm, March 2013” by Martha Sherwood. All rights reserved

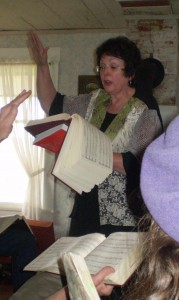

Image #2: “Karen Willard leads a song” by Martha Sherwood. All rights reserved.

Image #3: “O Come Away,” from The Sacred Hqarp. Public Domain.

Hey, Martha — This is an interesting article. I didn’t realize your introduction to shape note singing was so fortuitous. Glad you stayed!

Cheers, Suzanne

Martha, this is an eloquent description of the attraction of shape-note singing. Your article contains just enough history of shape-note singing to anchor it in the imagination, and give the reader a believable basis for its popularity. Your experience of a fundamental human community through shared rhythm and melody is meaningful to me and, I believe, to other readers.

I first came across Shape note singing when I hung out the original band members of a famous and musically inventive rock and roll band. Some of the players told me that their earliest singing experiences were with church music built on shaped notes…the history seemed to be that shaped notes preceded pianos and organs on the journey from the Old World to the new colonies. Seems like s great experience to explore. Thanks for writing about it.

Precedes pianos anyway, because they weren’t around in Europe either in colonial times. Small upright organs with a treadle pump, so much a fixture of small churches in the 19th century, weren’t around either. A large urban church could afford a full scale pipe organ but for a parish church they’d rely either on a string ensemble or sing a capella, and the shape note system made it possible for a congregation to sing in four part a capella harmony.

I think one of the reasons this type of singing is undergoing a revival is that competent accompanists for amateur singers are a dying breed. When I was in gradeschool in the fifties all our classrooms had pianos and most schoolteachers could play them well enough to facilitate group singing but that is no longer the case.