‘You can’t go home again,’ Thomas Wolfe wrote in his famous 1940 novel that carried the phrase as its title. But for writers the greater truth may be that you can never leave home. Or that home never leaves you.

I recently had the pleasure of co-leading a “Writing Home” workshop for the Writers Guild of Alberta with my colleague Judith Williams, an international award-winning author of non-fiction for young readers.

I recently had the pleasure of co-leading a “Writing Home” workshop for the Writers Guild of Alberta with my colleague Judith Williams, an international award-winning author of non-fiction for young readers.

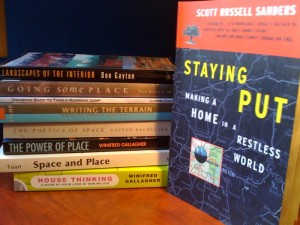

It was fun to pull some highly influential books from my shelves and revisit writers’ perspectives on writing about place. I quickly accumulated quite a stack of sources – more than I could even touch on in the afternoon workshop.

A favourite starting point is Scott Russell Sanders’s “Staying Put: Making a Home in a Restless World,” a lyrical exploration of the meaning of home, home towns, and home terrains.

As Sanders says in his preface, “the geography of land and the geography of spirit… are one terrain.” In the first chapter, Sanders returns to the now-flooded territory of his childhood, on the Mahoning River in Ohio. “Of course, in mourning the drowned valley I also mourn my drowned childhood,” he writes, but quickly shifts beyond mourning. “Loyalty to place arises from sources deeper than narcissism. It arises from our need to be at home on earth.”

That sense of connectedness operates on many levels but perhaps our strongest emotional attachment is to our home spaces – particularly the rooms and houses of our childhood (a topic of an earlier blog.)

Talking of the house where he and his wife have raised their daughter, Sanders observes that “these walls and floors and scruffy flower beds are saturated with our memories and sweat. Everywhere I look I see the imprint of hands, everywhere I turn I hear the babble of voices, I smell sawdust or bread, I recall bruises and laughter. After nearly two decades of intimacy, the house dwells in us as surely as we dwell in the house.”

The house dwells in us. The house also literally enables – it gives us the capability of forming our humanity in certain directions and ways. The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote about this in ‘The Poetics of Space,’ a difficult (at least for non-philosophers like me) but intriguing book first published in 1958.

In our workshop, we each took a moment to share an example of a meaningful place from our lives. Judith Williams talked of growing up in Quebec and being intrigued by her father’s wardrobe with its deep drawers. Inside one she saw a pile of papers. He was, she discovered, writing a book.

A new possibility appeared – an ordinary person could write a book.

Bachelard also uses the example of wardrobes, suggesting that they are not just a metaphor for a sense of intimacy and privacy but that their very existence allows us to learn those concepts. In other words, Bachelard would claim, if we don’t have the experience of private and ‘hiding’ places, we are incapable of experiencing privacy in the same way.

The spaces around us don’t just reflect our writerly ideas – they form them, enable them.

We write about our homes but long before that our homes write us.

Photo Credits

Books – Courtesy Of Lorne Daniel

Thumbnail and Feature Image from the Microsoft Clip Art Collection

Beautifully put. Thank you, Lorne.

Bobbi Ann Mason, “In Country” etc. once wrote that not only can you go home again, you must! if you are to be a writer, an artist. I always figured she meant go inside and find out where you came from – in country . Thoughtful piece, Lorne…and Ih aven’t seen Bachelard quoted or referenced in 30 years…ah, the poverty of my existence.

Thanks Michael – and you’re right, Bachelard is one of those writers that most of us visit in our university days and then never again. Just read a comment from the late / great Alberta writer Robert Kroetsch where he said that, for him, place is the most fascinating subject because it so defines us. I think I agree.