This is Part 2 of the series Afghanistan Calling by Allan Cram, a writer and helicopter pilot who has worked in some of the world’s most dangerous places. To read Part 1, click here.

The small helicopter company had kept to their word in providing as much information to us as possible, and in late June, before any of us had signed on the dotted line, they hired a Security Consultant from England to provide a Kidnap and Ransom (K&R) seminar. Here, the ex-SAS consultant outlined the hazards of Unexploded Ordinance (UXO) and land mines. He showed videos of suicide bombers in Iraq, and advised us that although it occurs in Afghanistan, it is rare.

We learned about criminal activity in Kabul, the dangers of travelling at night, of congregating in groups and of frequenting “ex-pat” nightclubs and restaurants. He gave us a list of private security firms established in Kabul. Ex-British or Dutch SAS officers — quiet, competent and highly trained. The five firms he mentioned all had web pages and I had looked up each one and read their list of accomplishments, projects and areas of expertise. I had worked with a British security firm in Sudan and my confidence went up in the belief we would be working with one of these premier companies.

We learned about criminal activity in Kabul, the dangers of travelling at night, of congregating in groups and of frequenting “ex-pat” nightclubs and restaurants. He gave us a list of private security firms established in Kabul. Ex-British or Dutch SAS officers — quiet, competent and highly trained. The five firms he mentioned all had web pages and I had looked up each one and read their list of accomplishments, projects and areas of expertise. I had worked with a British security firm in Sudan and my confidence went up in the belief we would be working with one of these premier companies.

When I asked about procedures in the event we were kidnapped, he dismissed it outright. “Kidnapping is not an MO of the Afghan culture,” he said. “It is very unlikely to happen.”

There was nothing else to do but pack up and go to Afghanistan and see for ourselves!

The first crew and aircraft were loaded on a large cargo plane in July 2007, and I went back to Thailand to finish my last offshore tour. I had prepared myself for some healthy criticism from my colleagues — after all, who in their right mind would leave sunny, smiling Thailand for a war zone?

And this is where the first of many things started to go pear-shaped.

While convincing my colleagues in Thailand, and myself, that I’d made the right decision, two German engineers had been kidnapped on July 18 only a few miles from Kabul. And the very next day 21 South Koreans had been abducted on the Kabul to Kandahar highway near Ghazni — a Taliban stronghold.

So much for the so-called insight of our security consultant.

And then I began to get email messages from the crew on site in Kabul about the difficulties they experienced off-loading the aircraft, of an emergency landing they had to make (after agreeing that all territory was like a shark-infested ocean), and of an array of names and groups that all seemed to have some claim to the helicopter and the crews.

Operational control of the aircraft had been identified as a problem with the previous contract. The pilots and engineers had lived with the customer — the construction company — and that may have contributed to some poor decisions that led to the three accidents. Of course, in Canada, helicopter pilots and engineers often live with the clients. On an exploration job we live in a camp provided by the geologists, geophysicists or drillers.

I’ve been on many jobs where I have been included in daily planning sessions, and my natural curiosity has enabled me to learn about geology, seismology, diamond drilling and forest fire behaviour. On forest fires, a good pilot should know as much, and sometimes more, than the suppression officers. Eventually one becomes a much more efficient pilot, often anticipating the needs of the drillers, the fire boss, the head geologist. But this close association can also lead to some poor decisions.

In Afghanistan, this close-knit group hadn’t become more efficient — at least not from the outside. When three helicopters were destroyed while on the same contract, something was fundamentally wrong.

The first helicopter had destroyed itself in a brownout — a dust ball created by the downwash when landing, and the pilot had lost all spatial orientation. This can happen easily, and quickly, and if the pilot isn’t prepared for it, or doesn’t know what to do when it happens, a rollover is inevitable. Any pilot who has heli-skied in the fine powder snow of the mountains knows all about losing spatial orientation.

The second machine was destroyed when the construction company engineers had flown to a small village to meet the elders to discuss reconstruction plans. As they were leaving, two insurgents emerged from the crowd that had gathered to watch the helicopter leave and they sprayed the machine with 49 rounds from their AK-47s. The pilot was killed and several others were wounded. I knew that pilot, having flown with him in Yemen some years back.

The Taliban destroyed the third machine in April 2007 after an emergency landing in the Ghazni Province south of Kabul. Insurgents had chased the pilot and the passengers up into the hills, and when it was clear they were not going to successfully capture or kill them, they returned to the abandoned helicopter and launched a few Rocket Propelled Grenades (RPG’s) into it, creating a three million dollar bonfire. NATO helicopters rescued the pilot and passengers several hours later.

The crew in Afghanistan and I began messaging each other and each day more and more names appeared who seemed to have some claim on our operation. When asked to clarify who all these people were, the other crew were unable to figure it out themselves. The major blow came when I learned that none of the “premier” security companies the security advisor had mentioned to us had anything to do with the construction company and our helicopter contract.

But I had quit my job in Thailand and had to remain optimistic — after all I had worked in some bizarre countries and knew that international operations sometimes appeared more confusing than necessary. I kept reminding myself that we would be operating along the highway from Kabul to Kandahar — well out of the combat zones in the south of the country. “It will be a walk in the park,” I said to my family, confident that I could untangle the mess.

Then — less than a week before I was scheduled to fly to Kabul — I received the first detailed report from the other aircrew. In addition to the expectation that we were to attend a weapons training course upon arrival, the construction company — our end-client — finally told the other crew that the Kabul to Kandahar Highway project had been completed for two years, and the helicopter would spend 60 to 70% of its time servicing the Kajaki Dam, a hydroelectric facility located in the northern part of the Helmand Valley. This is the valley where 82% of the world’s opium is grown, where British troops clung to the high ground and fought off daily Taliban attacks.

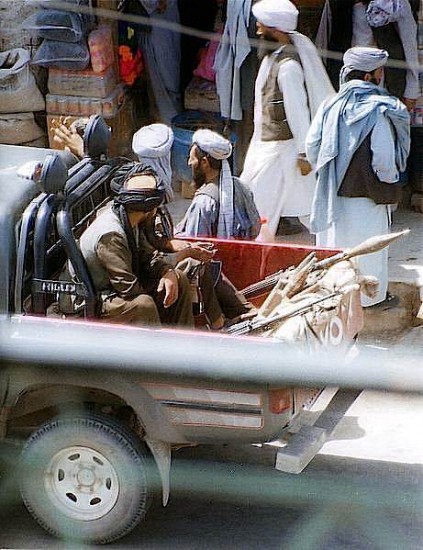

To get to there we would have to overfly some of the most perilous terrain in the world, where kidnap victims had little hope of being released alive, where Taliban extremists believed math should be taught to Afghan boys not by the adding or subtracting of apples and oranges, but by counting bullets and AK-47s.

If little Azul has two magazines holding 30-rounds each, how many infidels can he kill if he has a 45% accuracy rate?

No, this clearly wasn’t playing out the way I had been promised.

Photo Credits

“Green Acres” photo courtesy of Allan Cram. All Rights Reserved.

“Taliban” Wikimedia Commons.

Please Share Your Thoughts - Leave A Comment!