Following the release of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967, Bosley Crowther, film critic of the New York Times for 27 years, wrote a short but devastating review. In it he called the movie “a cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy that treats the hideous depredations of that sleazy, moronic pair as though they were as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cutups in Thoroughly Modern Millie.” Following Crowther’s review and others that were equally dismissive, the film was removed from distribution.

Following the release of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967, Bosley Crowther, film critic of the New York Times for 27 years, wrote a short but devastating review. In it he called the movie “a cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy that treats the hideous depredations of that sleazy, moronic pair as though they were as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cutups in Thoroughly Modern Millie.” Following Crowther’s review and others that were equally dismissive, the film was removed from distribution.

But the tide of negative criticism was stemmed and ultimately reversed by younger critics like Roger Ebert and Pauline Kael, the former calling it “a work of truth and brilliance,” the latter penning a long piece in the New Yorker defending the movie as “the most excitingly American movie since The Manchurian Candidate.” As a result, Bonnie and Clyde was re-released and went on to become one of the most popular and critically acclaimed movies of the 1960s. Bosley Crowther was replaced at the Times in early 1968.

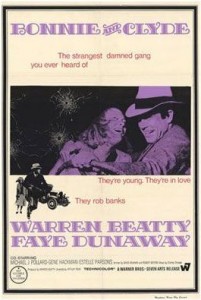

Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty play the infamous Depression-era couple who from 1931 to 1934 blasted their way through five states, stealing cars, robbing banks, and killing numerous police officers before finally meeting their end in a barrage of machine gun fire. In the brief span of their life on the lam Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow became outlaw legends despite the fact that they were pitifully, and sometimes comically, inept bank robbers.

Part of their allure came from the belief that Bonnie and Clyde were lovers, and in the movie they are indeed engaged in a rather adolescent romance and live pretty much as a couple. But Clyde is impotent, so to Bonnie’s increasing frustration, for most of the film the relationship is not consummated. If Clyde had not been able to finally perform the act, which in defiance of all narrative logic he was, the viewer might think that the impotence represented Clyde’s failure as a bank robber and as a human being.

The film is populated with a cast of hangers-on, including C.W. Moss (wonderfully played by the baby-faced Michael J. Pollard), a composite of three real-life Barrow gang accomplices, Clyde’s older brother Buck (Gene Hackman), a petty criminal who gets caught up in Clyde’s misbegotten vision, and Buck’s wife Blanche (Estelle Parsons, who won the Academy Award for best supporting actress for her role in the film). Bonnie and Clyde’s nemesis is Frank Hamer, the Texas Ranger who tracks them down and participates in their execution; Hamer is played by Denver Pyle.

In her essay in the New Yorker, Pauline Kael posed this question to critics who claimed the film glorified criminals: “Why the protests, why are so many people upset (and not just the people who enjoy indignation), about ‘Bonnie and Clyde’, in which the criminals are criminals, Clyde an ignorant, sly near-psychopath who thinks his crimes are accomplishments, and Bonnie, a bored, restless waitress-slut who robs for excitement?”

The problem with Bonnie and Clyde is not its realism; the fundamental flaw of the movie is that it attempts to create an interesting story out of essentially uninteresting characters. There is nothing about “an ignorant, sly near-psychopath” or “a bored, restless waitress-slut” that moves me no matter how stylish, how fresh, how realistic the filmmaking approach. Bonnie and Clyde are shallow, self-centered children out on an extended joyride that happens to involve the brutal killing of other human beings; neither is better or worse at the end of the film than he or she was at the beginning.

At no point in this movie do I feel like laughing or crying; at no point am I moved to ponder the effects of the Great Depression on the already poor; at no point do I care what happens to the protagonists.

Bonnie and Clyde recorded their exploits on film and in doggerel, “dramatizing their lives” for an eager audience of newspaper readers and thereby propping up their own fragile egos. It is certainly possible to understand the interest of an impoverished American public in a pair of anti-heroes who are sticking it to the establishment and its lackeys. At a distance of thirty, fifty or eighty years, however, they must surely be seen as the cardboard characters they truly were. If I am mistaken in this view and there was a measure of depth to Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, this movie has failed utterly to capture it.

Photo Credits

Movie Poster @ Wikipedia

Recent Ross Lonergan Articles:

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Four

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Three

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part Two

- The Film-School Student Who Never Graduates: A Profile of Ang Lee, Part One

- Bullying, Fear, And The Full Moon (Part Four)

Please Share Your Thoughts - Leave A Comment!