I am a hard-core unabashed book lover. There is something about the physical printed word for which other media can never fully substitute. At any given time, an electronic resource may well be more accessible, but over the long haul, hard copies will win out.

I am a hard-core unabashed book lover. There is something about the physical printed word for which other media can never fully substitute. At any given time, an electronic resource may well be more accessible, but over the long haul, hard copies will win out.

I was raised among books. My parents were both English professors, and they lined the walls of their large house with an amazing and eclectic collection of volumes, much of it of a scholarly nature. There were no Harlequin romances under the parental roof. A librarian would probably have looked at this private library and pronounced it outdated and irrelevant, but as a young child in grade school I didn’t know any better. I devoured books on history, geography, and science published fifty or a hundred years before I was born, and acquired a frame of reference more suitable to an adult living before the First World War than to a ten year old child in Eugene Oregon in 1958.

One of my prized possessions is my grandfather’s set of the 11th Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, purchased new in 1911. When writing papers in high school, I learned to rely on it heavily, because it was so much more complete and accurate than the newer encyclopedias in the school library. I also learned to conceal the fact that I relied on it, because of a general prejudice that existed even then against anything except the newest information source.

I started noticing discrepancies, particularly the way in which pieces of the past seemed to simply disappear from view, without explanation. The excuse given — that so much is happening now that something needs to be mothballed — rang false when I could see that large type, uninformative verbiage and arbitrary illustrations meant that my textbook’s coverage of the Second World War contained less concrete factual information than the century-old textbook had on the War of 1812.

If I had come into a Cold-War era World History class without the prior frame of reference, I would probably have accepted the narrative in our textbooks as the unvarnished truth. Some of my classmates still do, not having approached the learning experience with skepticism at the outset and not having formally studied history and science since leaving high school. Those textbooks have long since been consigned to the junk heap, but the attitudes they fostered are still evident in the voting patterns of my generation. Since these were books with US copyrights, copies still presumably exist in the Library of Congress, but a person doing scholarly research on how ideology influences pedagogy would be hard put to find a copy elsewhere.

In the 1960s, rewriting a textbook was still a big deal, requiring that the author retype the revised copy and the typesetter manually key in the changes. The amount of physical effort and technical expertise required to produce a book has declined dramatically in recent years, while the amount of effort required to produce thoughtful, well-researched text has not. As a result, the publishing world is inundated with ephemeral new editions and compilations.

In the 1960s, rewriting a textbook was still a big deal, requiring that the author retype the revised copy and the typesetter manually key in the changes. The amount of physical effort and technical expertise required to produce a book has declined dramatically in recent years, while the amount of effort required to produce thoughtful, well-researched text has not. As a result, the publishing world is inundated with ephemeral new editions and compilations.

Electronic publishing is a great boon to certain sections of the publishing industry, and to the public. Catalogs and telephone directories need constant updating. Real-time text-based news feeds with internal links put a wealth of information at a person’s fingertips. Specialized articles generated outside of Academe, which would even a few decades ago have remained in manuscript, unread and unnoticed, can reach a wide audience through the Internet.

There are problems, however, with relying on an essentially ephemeral medium to be the repository of timeless knowledge. Enormously detailed data sets, laboriously gathered, can disappear utterly, inadvertently or perhaps purposefully erased, destroyed when a hard disc crashes or stored tapes and discs deteriorate, or rendered inaccessible due to technology change. Because of the author or researcher’s low level of engagement with the product, human memory is not as helpful in data retrieval as it would have been if the material were actually written out.

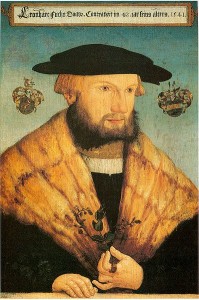

Another contrast between printed books and electronic media, which I encountered in my own research, is the issue of access. Not long ago I was working on two separate projects. One of these involved Leonhart Fuchs’ De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignis, first published in Basel in 1542 and a landmark in the history of science. The other was a current cutting edge topic in the biological sciences. A scanned copy of Fuchs’ beautiful herbal is available on line, but our library also had the original in its rare book room, where I could have consulted it. There are several hundred copies of this early printed book still extant after nearly five hundred years.

Cutting edge biology proved inaccessible to an independent researcher. Until recently I was able to use more recent journal acquisitions in the sciences, by physically going to the library and taking the journal off the shelf, but the library now gets many critical journals only in electronic form and access is restricted to faculty and current students. Electronic media tend to be either extremely available or highly restricted, with the restrictions only apparent to a person with a research background.

I fear that the ease of accessing information electronically is producing a generation of people who fail to notice discrepancies and gaps in the record, because they have less of an internal memory bank upon which to rely.

Image Credits

Books In A Stack @ Flickr

Leonhart Fuchs @ Wikipedia

I too am a lover of the printed word on real paper. So many of my peers have abandoned the bound words of an honest to goodness book in favor of a Kindle or some other e-means of reading. For me I’m trying to reduce my screen time, not increase it with the luxurious pleasure of reading a great book.

Thank you for starting the conversation Martha!