He first saw her in the soft light of early evening, surrounded by noise and hectic traffic, working the street in Bangkok on Sukhumvit Soi 7 at the tender age of seven.

He first saw her in the soft light of early evening, surrounded by noise and hectic traffic, working the street in Bangkok on Sukhumvit Soi 7 at the tender age of seven.

It was 2005 and her name was Pang Kam Sao, otherwise known by the beautifully lyrical title, Nong Pleum.

Englishman John Roberts was captivated by her poise and manner, a gentle young soul with big, expressive eyes hooded by long, dark lashes that would be the envy of any would-be Hollywood starlet.

Nong Pleum’s natural beauty and charm were being prostituted on the steamy city streets of the Thai capital and Roberts found he could not walk away from it. He could not leave her in that situation.

Nong Pleum was John’s first rescue.

There have been others since. But by virtue of her status, she is one of John’s special daughters.

Nong Pleum was with three people that evening, one of them a mahout.

Her unique and gentle beauty was being used by them to make money. They were selling small sticks of sugar cane, which passers-by and tourists bought to feed to her. Occasionally they took photos.

Over the next month, Nong Pleum and her mahout, Khun Lord, were arrested four times by the Thai Elephant Conservation Centre‘s elephant rescue team and moved to the countryside beyond the city limits.

They went to Pattaya to work the streets. When they were thrown out of Pattaya, they returned to Bangkok to work the streets. It was a never-ending cycle and no life for a baby elephant.

John finally convinced Khun L ord to bring Nong Pleum north to live in Chiang Rai at the elephant camp at the Anantara Golden Triangle Resort.

ord to bring Nong Pleum north to live in Chiang Rai at the elephant camp at the Anantara Golden Triangle Resort.

“His wife Khun Nang still wells up with tears whenever she thinks about separation from her beloved Nong Pleum,” John said.

Today, the Anantara Elephant Camp is home to 34 Asian elephants, 53 mahouts, a dozen wives and as many children.

The settlement is, in many ways, a testament to the clear thinking and dedication of John Roberts.

Roberts, 36, is an unassuming, well-spoken Englishman. In London he wouldn’t look out of place in a black suit and a bowler hat.

But in Northern Thailand, his business brief is a little different. There aren’t too many men in the world who can flash you a business card with the title, Director of Elephants.

To say that John has a large business portfolio is an understatement.

Not only is he the overseer of the Anantara Elephant Camp, he has also made it his life’s work to help save Thailand’s itinerant elephants from begging on the streets through the establishment of the Golden Triangle Asian Elephant Foundation, which provides a safe haven for out-of-work and abused elephants.

At any one time, up to 300 elephants and their mahouts are living and working on the streets of Bangkok and other big cities in Thailand, says John.

elephants and their mahouts are living and working on the streets of Bangkok and other big cities in Thailand, says John.

He and his mahouts do what they can, where they can. But his solution is far from free food and board. Everybody works, including the mahout’s wives. The elephant camp is a mahout community where the biggest members of the family are elephants.

Along with the tourist-focused mahout training program, annual elephant polo tournaments and other associated elephant-interactive activities, the wives and girlfriends of the camp have started a silk worm farm and a cottage industry spinning silk to make scarves and silk mobile phone and blackberry pouches.

John believes this approach to elephant conservation is more socially scientific than emotional, but there is no hiding the tender respect in his eyes as he interacts with some of his massive charges.

The most satisfying outcome of the elephant foundation so far is more to do with the culture than the elephants, he says.

“It is being able to sit here in the elephant camp and watch the Thai mahouts, their wives, children and their elephants go about a largely traditional way of life, albeit with selected modern amenities, in comfort and safety,” he said.

“This camp enables them to work their elephants, but not too hard. To get by financially and to be in a position to choose what to do for the next generation, of both their children and their elephants.

“We approach things in a more  pragmatic, scientific, conservationist manner, rather than running on pure emotion.”

pragmatic, scientific, conservationist manner, rather than running on pure emotion.”

It is a sweeping concept for a man who moved to Northern Thailand seven years ago, who was born in Somerset, England, and spent much of his early childhood hiking with his family in the rolling green hills of Devon and in Exmoor National Park.

John’s university engineering degree isn’t much use when he is crunching pachyderm fodder figures in the dusty, bamboo-frame loft he calls his office, in the roof of an elephant barn at the jungle camp below the Ananata Golden Triangle Resort.

He has worked as a volunteer in national parks in Nepal, and in Australia in Queensland and the Northern Territory, he has worked as a casual ranger, boreman and fencer.

John moved to Northern Thailand to live in 2002 to take up the role of Director of Elephants, his first full-time, paying job.

In Nepal, he was a volunteer field officer for Tiger Tops Jungle Lodge in Chitwan National Park. He worked in tiger research, “more collation of data than hard-core tracking”, he says.

“It involved lots of walking and taking guests out on elephants into the jungle.

“I guess I have always been interested in conservation. I studied an engineering degree because I thought it was the most difficult challenge I could face. But my heart was never really in it.”

John met his first Asian elephant in October, 1999, on the lawns at Tiger Tops.

“He was Sham Shere Bahadur, the largest domestic elephant in Nepal. He was a magnificent beast.”

From that introduction evolved John’s passion and dedication to make some kind of worthwhile contribution to the future survival of Asia’s elephants.

Today in Thailand, it is estimated that only around 1500 elephants are left in the wild and the survival of the estimated 3,600 domesticated elephants is threatened by in-breeding and a diminishing gene pool.

In 1900, the Thai elephant population was estimated at around 100,000 but within 50 years, that number had halved to 50,000.

John found his focus on the streets of Bangkok.

One would think that taking an animal the size of an elephant into a big city would be totally illogical and impractical. It is, but it is still done, and the motivation is quite simple – money and survival.

Elephants are expensive t o keep. A young adult needs to eat between 250kg and 300kg of fodder a day. Over the past few decades, reductions in the forestry industry and logging in Thailand has reduced traditional work for elephants and their mahouts.

o keep. A young adult needs to eat between 250kg and 300kg of fodder a day. Over the past few decades, reductions in the forestry industry and logging in Thailand has reduced traditional work for elephants and their mahouts.

Money can be made in the cities from tourists and Thais who wish to pat, feed and have photographs taken of themselves with these symbolic and revered beasts.

But for the elephants, the suffering far outweights the attention and homage – constant noise, negotiating fast-flowing, chaotic traffic on slow, cumbersome legs, standing and walking on hot, sun-baked bitumen day after day and snatching sleep under expressways and bridges.

Thai mahouts from the north-eastern Surin region of Isaan and their elephants, which grow up with and are part of the family, are often at the mercy of city racketeers and con-men who make big dollars from elephant entertainment.

The bigger tragedy is that there is often a tendency to split baby elephants from their mothers before natural weaning age. The babies survive, but lack of mother’s milk and calcium damages their development and health.

The reasons are simple: baby elephants are cute and so can be used to earn more money. They are also smaller, easier to transport and cost less to maintain and feed, as John says, “if you don’t intend to do it properly”.

“There is no point in buying an elephant to get it off the streets because it just places another one in danger. That is why we take the approach of encouraging the mahout, his family and the elephant to come to the elephant camp,” he says.

“We are closer to the attitude of the mahouts themselves and aim to work constructively for the whole – elephant, mahout and family.

“What the Golden Triangle Asian Elephant Foundation does is seek to rent these street elephants, offering their mahouts incentive to move their elephant and family to the elephant camp to live and work.”

Saving baby elephants is an expensive exercise.

Beyond the support provided by the resort, it costs about US$12,000 a year to feed and keep a rescued elephant.

Significant support for the elephant camp comes from money raised by Anantara through the annual Kings Cup Elephant Polo Tournament and from guest and corporate donations.

Individual donations are also accepted and A nantara guests can make a voluntary US$1 donation per room per night to help fund elephant projects.

nantara guests can make a voluntary US$1 donation per room per night to help fund elephant projects.

Tips left by visitors at the elephant camp are pooled and distributed between the mahouts and their families.

Over the past six years, the elephant camp has also created a micro-economy for surrounding villages and become a focus for specialist veterinary training.

The camp is located on a 160-acre tract of jungle and floodplain straddling the borders of Mayanmar, Laos and Thailand in the Golden Triangle, but the area cannot sustain a herd of 34 foraging elephants, so fodder is constantly being purchased from surrounding villages.

“The camp generates income for surrounding villages which grow and supply food for the elephants including, sugar cane, bananas and pineapple tree fronds,” John said.

“An elephant eats about 10 per cent of its body weight every day.

“At about 250kg of fodder a day, that equates to around 10,000kg of food to feed a relatively small elephant for one year.”

Specialist elephant vets are a rare commodity in Thailand, says John, so an intern program has also been established at the camp to provide newly qualified vets with the opportunity to treat elephants.

As the sun rises over the Mekong River, slowly burning off the early morning mist on the flood plains, the muffled sound of stirring elephants and their mahouts can be heard at the Anantara resort, drifting up from the jungle below.

It is a moment of magic which has been played out over countless generations of elephants and their mahouts over Northern Thailand, reaching far back in history to the Kingdom of Siam.

The elephants stand quietly, flapping their ears to cool themselves in the rising heat, awaiting their learner mahouts – their real masters at their trunks.

They seem to know that the “training school” is something of a show for tourists. They patiently play along, no doubt looking forward to the bath in the lake after the 15-minute elephant walk along a jungle track.

They cumbersomely, but somehow delicately lower themselves and with the command “Song Soong” lift their right front leg up for their novice riders to use as a leg-up to perch on their broad necks.

The transition from earthbound tourist to trainee mahout is easier for some than for others. But after some huffing and puffing and a few indelicately-placed shoves from the mahouts, all the trainees are mounted and ready for the ride – the expressions on their faces ranging from amazement and pleasure to controlled apprehension and fear.

“The mahout training program is a sustainable, low impact way for elephants and mahouts to earn a living,” John explained.

Nong Raimon, a one-year-old female calf, is scampering around an enclosure on legs as thick as small tree trunks, for all the world like a playful puppy, much to its mother, Bua Tong’s, disdain.

Under one of the two-story high elephant barns the mahout Noi is feeding his elephant, Beau. They have been together for 21 years.

Noi’s father was a mahout, but he doesn’t want his four-year-old son to grow up to be a mahout. “No money,” he says, shaking his head. Chewing on sugar cane, Beau shakes her head, as if in agreement.

Noi’s father was a mahout, but he doesn’t want his four-year-old son to grow up to be a mahout. “No money,” he says, shaking his head. Chewing on sugar cane, Beau shakes her head, as if in agreement.

Under the thatched roof of another barn stands Punlab, continuously nodding, believed to be a sign of emotional stress.

Punlab, 23, was working in a trekking camp in Pattaya when she fell pregnant.

The gestation period for an elephant is 18 – 22 months, 12 months of which a cow cannot work. After giving birth, a cow feeds for up to three years, effectively making her unemployable for more than four years.

So pregnant Punlab and her mahout were kicked onto the streets, but fortunately, were later rescued and taken to the elephant camp.

Her offspring, Lynchee, is now three. She is John’s “special daughter”.

“I have a special affectio n for her and she has a special affection for me,” he said, almost embarrassed. “It’s probably because she was the first baby we had here, and I allowed myself to spoil her rotten before we got all scientific.”

n for her and she has a special affection for me,” he said, almost embarrassed. “It’s probably because she was the first baby we had here, and I allowed myself to spoil her rotten before we got all scientific.”

But being “scientific” isn’t always easy.

That became painfully evident a few years ago, on a visit to Surin in north-east Thailand, a 14-hour drive through the mountains from Chiang Rai.

Hundreds of domesticated elephants and their mahouts make their way to the Surin Elephant Round-Up every year, a vibrant mix of culture and tourist theatre. Surin Province is the home of the Kui, a tribe originally believed to have migrated from Cambodia, which has traditionally tended and trained Thai elephants for centuries.

“The second elephant we rescued was Tawan,” John said.

“He was in hospital in Surin after being hit by a car while begging on the streets.

“We quickly raised 180,000 baht to purchase him from the mahout to bring him back to the camp.

“A year later, I met the same mahout in Surin and he approached me with two baby elephants for sale. He had bought them with the money we had paid him for Tawan, plus a little insurance money from the driver of the car that had hit the elephant.

“One of the hardest things I have had to do was to turn him and his baby elephants away.”

Please read Part 2 of The Elephant Man, How to Talk to Elephants.

For more information on elephant sponsorship, visit the Golden Triangle Asian Elephant Foundation website; for mahout training and other elephant camp activities, visit the Anantara Golden Triangle Resort and Spa website.

Photo Credits

Bua Tong with baby Nong Raimon © Vincent Ross

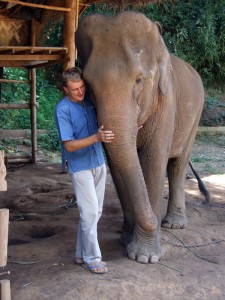

Director of Elephants John Roberts and Punlab © Vincent Ross

1 year old female calf Nong Raimon © Vincent Ross

Mahout Noi feeding his elephant Beau © Vincent Ross

Vegetable stealing – 1 year old female calf Nong Raimon © Vincent Ross

Chiang Rai – the elephant walk to the bathing lake at the elephant camp ©) Vincent Ross

Anantara Resort and Spa © Vincent Ross

1 year old female calf Nong Raimon © Vincent Ross

A trainee mahout mounting at the elephant camp © Vincent Ross

[…] story is Part 2 of The Elephant Man. For Part 1, please click here. Interaction between man and pachyderm is via specific commands and actions, […]